Regulatory loopholes allow more than 30 million pounds of a cancer-causing pesticide to be sprayed on U.S. crops.

By Caroline Cox

California regulators were stunned by their air monitor results in April 1990. Concentrations of a cancer-causing pesticide at schools in Merced County were so high that regulators immediately stopped any use of that pesticide in California. It’s a chemical with an unwieldy name, 1,3-dichloropropene, that you may have never heard about. But there are many reasons why you should be concerned about its use.

The pesticide, also referred to as 1,3-D, is still a problem three decades after I first wrote about it in 1992, when the detection of high levels of 1,3-D in the air of a junior high school led to serious concerns.

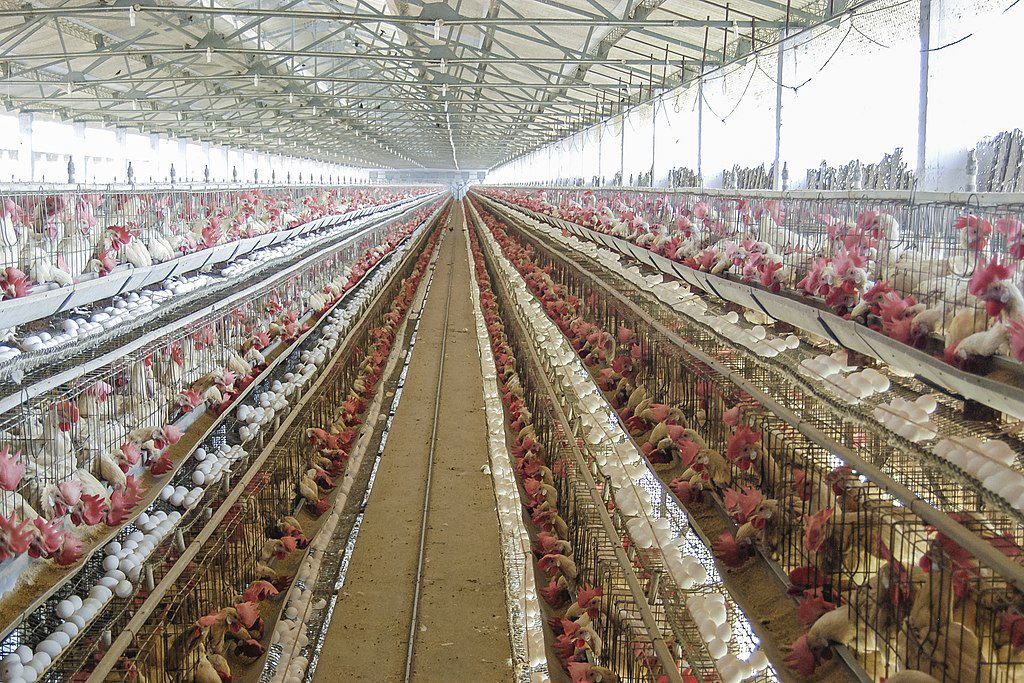

The use of 1,3-D in California was suspended from 1990 to 1995 but continued in the rest of the country. Since then, its use has come back with a vengeance. About 34 million pounds are used annually in the United States; about one-third is used in California. The use of 1,3-D is concentrated in the southeastern U.S., central California, and the potato-growing areas of Washington and Idaho. It is mainly used to kill nematodes, symphylans, and wireworms and control some plant diseases.

In California, the heaviest use of 1,3-D is for preparing fields to grow almonds, strawberries, sweet potatoes, grapes, and carrots. Nationally, potatoes accounted for about half of all 1,3-D used between 2014 and 2018, according to a 2020 United States Environmental Protection Agency report.

1,3-D is manufactured by just one company in the U.S., Dow Chemical, and is often sold under the brand name Telone.

Regulatory Loophole

The story of how and why regulators have allowed 1,3-D’s use to continue and even increase is a complicated one that involves politics, economics, and corporate power. For example, in 2002, California opened a regulatory loophole that allowed 1,3-D use to increase, leading to “unfettered 1,3-D access as its use spread to populated areas near schools, homes and businesses,” wrote Bernice Yeung, Kendall Taggart, and Andy Donohue in 2014 in Reveal.

“The loophole also expanded a key market for Dow, allowing it to sell millions more pounds of chemicals across a state that provides the U.S. with nearly half of all its fruits, vegetables, and nuts,” the article in Reveal added. Yet in 2016, limits on 1,3-D use in California increased again.

In 2022, the Office of the Inspector General at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that “EPA did not adhere to standard operating procedures and requirements for the 1,3-Dichloropropene, or 1,3-D, pesticide cancer-assessment process, which undermines public confidence in and the transparency of the Agency’s scientific approaches to prevent unreasonable impacts on human health.”

In other words, the agency did not do its job. This is in stark contrast to the European Union, where 1,3-D use is not approved.

Elaborating on the extensive use of the pesticide, the inspector general also stated that “1,3-D is one of the top three soil fumigants used in the United States.”

1,3-D Causes Air Pollution

1,3-D typically is applied as a liquid that is injected into the soil. It quickly becomes a gas, moves through the soil, and escapes into the atmosphere.

California is the only state that regularly monitors 1,3-D in the air around agricultural communities, but the few results that have been obtained are extremely concerning. Weekly air monitoring data that began to be recorded in 2011 and has continued as of May 2024 is available from four towns (Oxnard, Santa Maria, Shafter, and Watsonville) where the air monitors are located at schools.

In 2022, about one-third of the samples collected from these air monitors contained 1,3-D. Over the entire sampling period, the average 1,3-D concentration at the four schools was between .09 and .46 ppb. According to my calculations, this is double the safety level set by California’s scientists at the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) at the least contaminated school site and 10 times the safety level at the most contaminated school site.

1,3-D is classified as a hazardous air pollutant under the Clean Air Act and is also designated a toxic air contaminant in California. Regulators in California who modeled high detections of 1,3-D between 2017 and 2020 have found that 1,3-D can drift for more than 3 miles from where it is applied.

Clear Evidence of Significant Health Hazards of 1,3-D

Cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified 1,3-D as a cancer-causing chemical (“possibly carcinogenic to humans”) in 1987. In 1989, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) evaluated 1,3-D and concluded that it was “reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.” California made a similar classification in 1989. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health calls 1,3-D a carcinogen.

In a 2021 review, California’s OEHHA summarized laboratory studies conducted on rats and mice in the 1980s and 1990s, showing that exposure to 1,3-D caused tumors or cancer in multiple organs: lungs, tear glands, bladder, and breasts.

Asthma and Other Breathing Problems

Regulatory agencies recognize that 1,3-D irritates the lungs. The European Chemicals Agency states that 1,3-D is “harmful if inhaled” and “may cause respiratory irritation.”

The HHS concludes that the “[i]nhalation of dichloropropenes may cause respiratory effects such as irritation, chest pain, and cough.” California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation (CDPR) states, “Acute or short-term inhalation exposure to high concentrations of 1,3-D results in upper respiratory symptoms in humans, including chest tightness, irritated and watery eyes, dizziness and runny nose.” Researchers at the University of California, Merced, found that tiny increases in the amounts of 1,3-D in the air (0.01 parts per billion, or ppb) increased the odds of emergency room visits for asthma from 2005 to 2011.

Genetic Damage

As with cancer, evidence that 1,3-D can cause genetic damage has been available for decades. In 1987, WHO reported that 1,3-D caused genetic damage in mice, bacteria, and laboratory-grown cells from several mammals.

In 2021, California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment compiled studies of genetic damage and found evidence of it in mice, rats, bacteria, fruit flies, and laboratory-grown cells from hamsters and rats.

Environmental Injustice

California is the easiest place to evaluate environmental justice issues related to pesticides because this information is more readily available there than in other states. When I combined California’s pesticide use data for 2021 with demographic data from the U.S. Census Bureau for 2020, I found clear evidence that race and income play an important role in determining who is exposed to 1,3-D.

Of the 10 counties with the highest 1,3-D use, eight were above the state average for the percent of families living in poverty, nine had median incomes less than the state average, and eight were majority Hispanic/Latinx. The bottom line is that people who live in the areas where 1,3-D is widely used are likely to be low-income and Latinx. While the same detailed data is unavailable for the rest of the country, finding similar patterns would not be surprising if such information were provided.

And there’s more to the story in California. The state has set two different safety levels for exposure to 1,3-D. One was set by the CDPR, and the other by OEHHA. Both agencies set a safety level that is supposed to limit exposures to 1,3-D according to what they believe will only cause one cancer case per 100,000 people exposed.

CDPR’s number, focused on people who live near 1,3-D applications, is set at an average air concentration of 0.56 ppb. OEHHA’s number, which applies to everyone in California and is based on health-protective science, is an average air concentration of 0.04 ppb.

As a result, people who live in agricultural areas, likely to be low-income and Latinx, can be exposed to 14 times more 1,3-D than other Californians.

Climate Change Concerns

Dow in Freeport, Texas, manufactures 1,3-D at the largest chemical plant in the Americas. The plant was built to take advantage of natural gas wells close by. I have not come across an accounting of 1,3-D’s carbon footprint, but given that it is made from natural gas, I assume that the carbon footprint of the manufacturing process is likely to be significant. Millions of pounds of this chemical are transported thousands of miles using gasoline or diesel power, adding to the carbon footprint. Finally, the application equipment used for 1,3-D is typically diesel-powered.

Crops grown without 1,3-D and other fumigants can actually reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. A good example comes from research done in California almond orchards in August 2021. The scientists who conducted the study, published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, compared conventional almond orchards (commonly treated with 1,3-D) with regenerative, certified organic orchards that do not use 1,3-D or similar pesticides. The study found that organic orchards had 30 percent more carbon in their soil than conventional orchards and, therefore, helped in removing that carbon from the atmosphere and prevented climate change.

You Can Make a Difference

Like many people in the U.S., I live in a county where 1,3-D use is rare, or even zero. No crops grown near me use 1,3-D. But I also consciously choose to avoid eating food that harms people growing or harvesting such crops or those living near fields where they are grown. Fortunately, it’s easy to make a difference. I buy certified organic food as much as possible, especially potatoes and almonds.

Buying organic products is increasingly becoming a popular choice in the U.S., with more than 80 percent of Americans purchasing some organics in 2016, according to a study by the Organic Trade Association. Accessibility to affordable organics is also getting better. More and more standard supermarkets carry organics. In many states, SNAP benefits (food stamps) are doubled for fruits and vegetables, making it easier for SNAP customers to buy organics. Farmers markets, food coops, and community-supported agriculture are other options. The more we buy organic food, the less 1,3-D will be used.

Caroline Cox is a retired pesticide scientist. She was a staff scientist at the Northwest Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides from 1990 to 2006 and a research director and senior scientist at the Center for Environmental Health from 2006 to 2020. She is a contributor to the Observatory.

Photo Credit: Austin Valley / Wikimedia Commons