Read the rest at LA Progressive.

In education policymaking in Washington, D.C., the “bean counters” are still in charge.

By Jeff Bryant

Barely a month after President Biden was inaugurated, educators and public school advocates reeled in dismay when his administration announced it would enforce the federal government’s mandate for annual standardized testing in public schools. During the Democratic Party’s presidential primary, Biden had expressed strong opposition to the tests. In a video taken at a December 2019 forum for public school teachers, Biden, when asked, “Will you commit to ending the use of standardized testing in public schools,” replied, “Yes… You’re preaching to the choir.”

Although the decision was made before he took office, Miguel Cardona, Biden’s secretary of education, confirmed the Biden administration would not allow states to skip the exams.

So what happened to “the choir”?

It’s not like there was a groundswell from across the country to resume the tests.

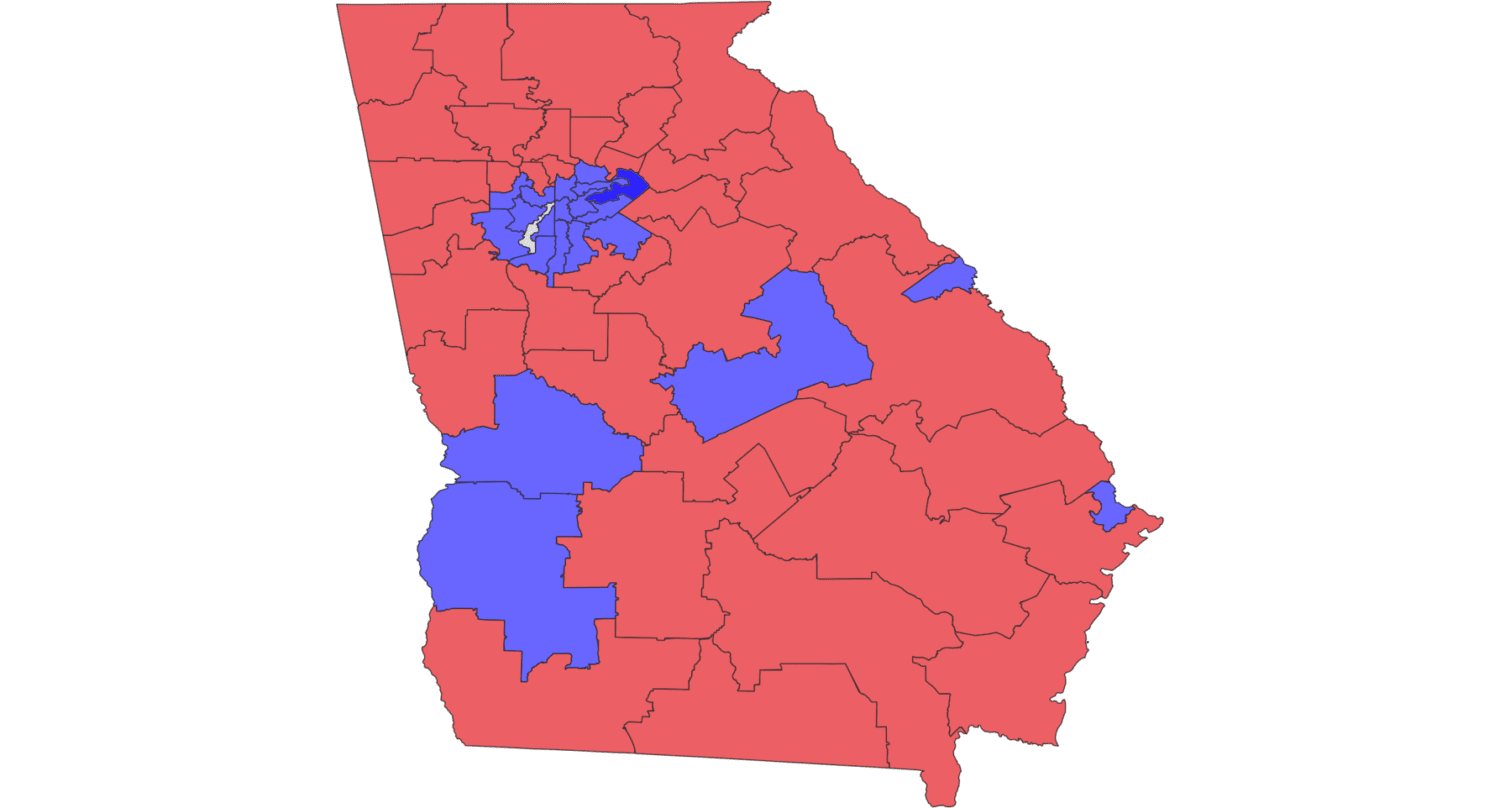

Prior to the Biden administration’s announcement, Chalkbeat’s national correspondent Matt Barnum reported, “Several states, including California, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York, [had] already asked for or said they planned to request a waiver from this year’s testing requirements entirely.” As of March 29, three states—Georgia, Oregon, and South Carolina—that had requested to offer alternatives to a statewide standardized test were denied, according to a later report by Barnum, but Colorado will be allowed to cut the number of tests it administers by half.

“The two national teachers’ unions—the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers—have urged that waivers be given,” Valerie Strauss reported for the Washington Post. “At least [11,000] people have signed a petition by the Center for Fair and Open Testing, a nonprofit organization known as FairTest, calling for waivers to be granted.”

A Backlash to the Biden Decision

The announcement on testing triggered an immediate backlash. “Critics reacted swiftly to the decision to require the exams, flooding social media with condemnations,” Strauss reported for the Washington Post. A notable critic, she pointed out, was New York City’s outgoing school chancellor Richard Carranza, who “urged parents to refuse to let their children take the tests.”

In surveys and widespread commentaries, teachers have long said the tests are of little to no use for their own teaching.

As education historian Diane Ravitch explains in the Washington Post, teachers see the scores months after the students have moved on to another grade, they’re not allowed to see the questions on the tests or how their students answered questions, and the tests don’t tell them which students need extra help, how their students compare to their classmates, or how they should change their teaching methods.

The tests are of little use to parents too, Ravitch states, because, other than ranking their children, the tests don’t inform parents about more urgent concerns for their children’s progress in school, such as how they’re keeping up with and understanding the work, participating in class, and engaging with other students and with the school community as a whole.

The tests have their detractors among state and local policymakers too, reports Barnum. Although “many states” had already been planning to go forward with the tests, Barnum reports, numerous state and local education officials signaled they may ask the federal government for “additional flexibility, or appear to have disregarded the department’s clear language entirely.”

More than 500 education researchers have asked Cardona to reconsider the mandate. Cardona has claimed that test results will “ensure that we’re providing the funds to those students who are impacted the most by the pandemic,” even though plans for distributing the funds have already been determined.

Members of Congress have also spoken out against the tests. Several Democrats led by Rep. Jamaal Bowman of New York have urged Cardona to reconsider the decision, Politico reports: “Bowman said that requiring testing this year would add stress to kids who are already traumatized and divert school administrators’ resources and attention away from reopening safely.”

This ‘Mentality’ Isn’t Going to Work

So who believes we need the tests?

One of the congressional Democrats who signed Bowman’s letter to Cardona, Rep. Mark Takano of California, previously gave me an interesting explanation for that.

In 2015, when President Obama’s Secretary of Education Arne Duncan was such a huge proponent of testing he insisted test scores be used to evaluate teachers, I interviewed Takano, who, like Bowman, had been a public school teacher before being elected to Congress.

When I asked Takano about what he called the federal government’s “test and punish” approach to education policy, he stated that the testing mandate, which began when No Child Left Behind was signed into law in 2002 but still dominates today, wasn’t “designed for the types of realities in [his] school.”

What do colleagues in Congress say when he tells them this? He told me the problem in Congress is that there are two types of people who tend to dominate Beltway ideology and the philosophy that drives problem-solving.

Most people, he explained, are either from the worlds of business and finance or they’re attorneys. The former, due to their work experiences, tend to be driven by numbers and production outputs, while the latter, due to their advocacy interests, want to remedy societal problems, including those that are obvious in the education system, by “putting into place a law with all these hammers” to make someone accountable for any statistical evidence of injustice and inequality.

Neither “mentality [is] going to work in education,” he told me, because at the heart of the education process is teachers being able to build trusting relationships with students and strategizing with other teachers on how to engage students. Having to hit a mark on the annual test or worry about an accountability measure closing your school or ending your employment just gets in the way.

A Pressure Campaign

Someone who fits the mold of those wanting to drop a hammer on educators is acting Assistant Education Secretary Ian Rosenblum, who signed the letter informing state education departments of the decision to carry on the testing mandate.

Rosenblum came to his position having previously served as executive director of Education Trust–New York. Prior to that, he had worked in the administrations of two governors who pushed standardized testing in their states, Andrew Cuomo in New York and Ed Rendell in Pennsylvania.

Rosenblum’s previous organization is part of the national Education Trust, which is currently led by John King, who was secretary of education in the Obama administration after Duncan.

In the run-up to Rosenblum’s announcement, the Education Trust organized a pressure campaign with a coalition of other like-minded organizations to advocate for the tests. As the campaign rolled out, the coalition expanded from a dozen civil rights and disability advocates to more than 40 groups with a broad spectrum of interests, including business, civil rights, charter schools, politics, and so-called education reform policies.

In a series of three letters sent to education department officials—in November 2020 and on February 3 and February 23, 2021—the argument the Education Trust and its allies put forth was that the “data” generated by the tests were “imperative” to determine how “scarce resources can be directed to the students, schools and districts that need them most” and “to address systemic inequities in our education system.”

In his letter upholding the testing mandate, Rosenblum repeated the identical theme: “we need to understand the impact COVID-19 has had on learning and identify what resources and supports students need. We must also specifically be prepared to address the educational inequities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.”

There are three reasons this argument is mistaken, at best, or, at worst, purposefully deceptive.

First, throughout the pandemic, it has been well understood that students who chronically struggle the most in schools—students of color, Indigenous students, English learners, immigrant students, students with disabilities, students from low-income families, and students experiencing homelessness—are the ones who have been further disadvantaged by the crisis. No one needs test scores to inform them of this harsh reality.

Similarly, the assertion that test data are needed to reveal the inequities of the nation’s education system is absurd. The inequities of the nation’s education system were stark and apparent to all before the pandemic. Obviously, a historic health and economic crisis will only worsen inequities.

Finally, the belief that standardized testing will lead to allocating education resources more effectively is simply not borne out in the history of standardized testing.

As New York City art teacher Jake Jacobs states in the Progressive magazine, “Not only have achievement gaps persisted or widened throughout the standardized testing experiment, so-called ‘help’ has never come, year after year. In fact, the original No Child Left Behind Act meted out escalating punishments, defunding and closing low-scoring schools, or placing them on closure lists to the delight of charter school developers and investors.”

The Biden administration has said that the test score data will not be used to discipline or punish low-performing schools, states, or districts. But does anyone really believe predictably low scores won’t become fodder in the ongoing campaign to dismantle public schools?

Follow the Money

Because of these flawed arguments behind the demand for testing, public school advocates are suspicious that federal officials are simply doing the bidding of private foundations and political groups that tend to influence education policy.

As evidence of that, Leonie Haimson, executive director of Class Size Matters, posted on Ravitch’s personal blog the names of all the organizations that signed on to the Education Trust’s pressure campaign and included the amounts of funding each has received from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation, two of the most influential philanthropies that have spent billions in an effort to transform K-12 education to conform to market-based policy ideas. Most of the organizations have taken donations from Gates and Walton foundations, and some have gotten tens of millions of dollars.

Another source of financial pressure could be coming from the testing industry itself.

Assessment companies have been estimated to rake in over $1.7 billion annually, according to findings from a 2012 Brookings Institution assessment, as reported by Education Week. A 2015 article by Valerie Strauss in the Washington Post reported that testing companies spent more than $20 million on lobbying state and federal government officials from 2009 to 2014 and frequently hired them to do their lobbying.

When former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, under Trump, allowed states to cancel tests in 2020, one of the larger test companies, Cambium Assessment, took a revenue “hit,” the company’s president told a reporter for Education Week’s Market Brief.

That article also notes that testing companies may take on additional “cost burdens” in 2021 because the Biden administration’s requirements allow states to make some modifications to the length of tests and when they can be given.

Regardless of the money trail and its influence, it’s not clear why the Biden administration made the decision to continue enforcing the testing mandate, and the effects of this perplexing call to continue testing during such an unprecedented school year could have far-reaching impacts, most of which, on balance, seem negative, while few seem positive.

One thing that appears to be certain though, is that, as Takano also told me, “If you liken education to bean counting, that’s not going to work.” And so far, the bean counters still seem to be in charge.

Read the rest at LA Progressive.

Jeff Bryant is a writing fellow and chief correspondent for Our Schools. He is a communications consultant, freelance writer, advocacy journalist, and director of the Education Opportunity Network, a strategy and messaging center for progressive education policy. His award-winning commentary and reporting routinely appear in prominent online news outlets, and he speaks frequently at national events about public education policy. Follow him on Twitter @jeffbcdm.