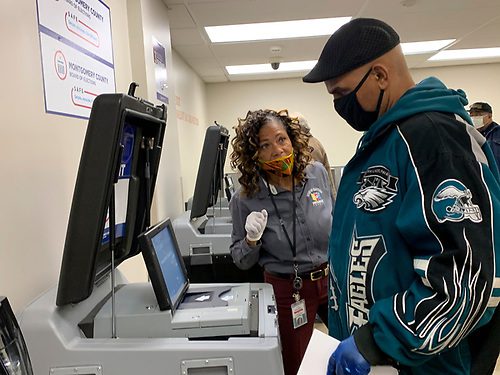

Cover photograph: Election worker Hazel Rountree explains how to place a ballot in the optical scanner on the first day of early voting in Ohio in October 2020. Photo © Sue Dorfman / Zuma Press. All rights reserved; used with permission.

Click to Read or Download the Full Report

Editor’s note: The Independent Media Institute and Voting Booth project are grateful for the support of Carla Itzkowich, in honor of her father, Moises Itzkowich, to produce special reports like these.

This fall, 60 percent of U.S. voters will have candidates on their 2022 ballot who support Donald Trump’s false claim that he won 2020’s presidential election. Meanwhile, pro-Trump activists and agitators are gearing up to claim the 2022 general election will be rigged unless election-denying candidates win. In Arizona last weekend, bogus stolen election claims based on made-up or irrelevant technicalities drew cheers and applause, underscoring that fervent partisans often do not understand how elections work. On Monday, provocateurs like Steve Bannon are encouraging Trump supporters to interfere and cast doubt on the vote-counting process if the GOP’s election-denying candidates lose.

This disturbing backdrop is why the Independent Media Institute’s Voting Booth project has produced an authoritative report explaining how today’s computer-based voting systems work. It explains the process—from designing ballots, to detecting votes on those ballots, to creating the subtotals and totals that add up to the results in every contest—and cites procedural errors that election officials make that have been exploited for results-denying propaganda.

The report, “Voting Systems: How They Work, Vulnerabilities, and Mitigation,” is co-authored by Voting Booth’s Steven Rosenfeld, a national political reporter who has specialized in election administration, and Duncan A. Buell, a lifelong computer scientist and more recently a county election official.“

Today’s voting systems have strengths and weaknesses. This report was created to explain how these systems work and to discuss vulnerabilities at key junctures that have been exploited by partisans seeking to sow chaos and doubt about the results,” it concludes. “It is the authors’ hope that readers—from voters, to trusted community leaders, to journalists, policy experts, and lawmakers—will better understand how elections are run and how votes are detected and counted and will bring an evidence-based mix of skepticism and realism to this foundational feature of American democracy.”

Excerpted from the report’s introduction:

Voting Systems: How They Work, Vulnerabilities, and Mitigation

By Duncan A. Buell and Steven Rosenfeld

The world of running elections is little understood and widely politicized. Partisans who do not understand the stages of the voting and counting process have been quick to criticize elections as illegitimate when their candidates lose. These critics have made unfounded claims about the operations of voting systems and actions of election workers. Their accusations ignore many of the checks and balances that catch administrative mistakes and are intended to ensure accurate results.

Still, election systems, like any large electronic infrastructure composed of subsystems, are not without vulnerabilities that can impede their operation or be exploited by individuals seeking to tarnish the process. One of the biggest problems shadowing the national update of voting systems (following Russian meddling in the 2016 election) has been procedural lapses that caused incorrect vote count results to be released soon after Election Day. These errors were not quickly acknowledged but propelled much of 2020’s election disinformation.

More specifically, the lapses were failures by election officials and their contractors to verify that the information and data in their systems have been accurately programmed and synced. This involves configuring the ballot layouts, the scanners that analyze the ink marks on ballots and assign votes, and the tabulators compiling subtotals into vote counts. When this information has been incorrect or uncoordinated, the unofficial results released immediately after Election Day have wrongly assigned vote totals. In most of the cases we know of, the errors were caught and corrected before the winners were certified. But these errors have fueled great partisan rancor.

When programming errors occurred in 2020’s presidential election in Antrim County, Michigan, a rural expanse with fewer than 24,000 residents, Donald Trump’s supporters claimed the initial incorrect tally reflected an untrustworthy election across the state. These partisans launched an investigation that reveled in stolen election clichés and which revealed a lack of factual knowledge of how election systems work. But because most voters do not know how elections are run, these and other false claims have lingered. As of fall 2022, tens of millions of voters still believe that President Joe Biden was not legitimately elected.

This report explains how the vote-counting pathways in the latest generation of election systems works, their technical vulnerabilities, and some remedies. Its authors have spent years studying elections in complementary spheres. Duncan A. Buell is a lifelong computer scientist and more recently a county election official in South Carolina. Steven Rosenfeld is a national political reporter who has specialized in election administration and voting rights.

The authors believe the public is best served by understanding the interrelated mechanics behind voter registration, casting votes, detecting votes on ballots, and compiling results. Today’s voting systems are layered and complex, and like the people who run them, they are not error-free. Thus, it is important that mistakes, where they occur, are understood, contextualized, and not exploited.

Today’s voting systems can produce an extensive evidence trail of every operation that follows the voter and their ballot. Not all of the data sets accompanying these steps are public records in every state. But many crucial records often are. Additionally, many election officials are not always comfortable with sharing the powerful data they possess—data that could attest to results and pinpoint and rectify problems. However, this report describes and deconstructs election infrastructure as transparently as possible to steer disputes to reality-based factors and evidence.

Duncan A. Buell is a visiting assistant professor of computer science at Denison College in Granville, Ohio. In 2021, he retired from the University of South Carolina, where he was a professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering and was department chair and interim dean. He served as a consultant to the League of Women Voters of South Carolina on election technology and analyzed Election Systems and Software (ES&S) election data from South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Kansas, North Carolina, and Colorado. He also was a consultant to Richland County, South Carolina, and Maricopa County, Arizona, on resource needs to prevent long lines at polling places.

Email address: [email protected]

Website: http://duncanbuell.org

Steven Rosenfeld is a national political reporter who has covered democracy issues since the 1990s. He has reported for Vermont newspapers, Monitor Radio, and National Public Radio, and many websites including BillMoyers.com, the New Republic, AlterNet, Salon, American Prospect, National Memo, LA Progressive, and others.

Rosenfeld turned to election administration after Ohio’s 2004 presidential election. In 2010, he was part of a Pew Center on the States team that designed the Electronic Registration Information Center, which 33 states and the District of Columbia use to update voter rolls and contact eligible voters. Since 2016, he has focused on the evidence trails in elections. He has written or co-authored six books on election topics, including 2021’s oral history, “The Georgia Way: How to Win Elections.” His reporting is distributed by the nonprofit Independent Media Institute, where he directs its Voting Booth project.

Email address: [email protected]

Website: https://votingbooth.media

The Independent Media Institute and Voting Booth project are grateful for the support of Carla Itzkowich, in honor of her father, Moises Itzkowich, to produce special reports like these.