Strong social networks foster resilience to food system shocks, both within and between Pacific Island communities.

By Stacy Jupiter, Teri Tuxson, Caroline Ferguson and Sangeeta Mangubhai, Independent Media Institute

4 min read

Pacific Islanders are no strangers to disasters. For millennia, island peoples have coped with and adapted to disasters like tropical cyclones and tsunamis, as well as unpredictable shifts in precipitation patterns, leading to droughts and floods.

Because most coastal communities across the Pacific region are found on low-lying atolls and narrow coastal margins, they are particularly vulnerable to—and adept at—coping with environmental extremes as a result of their adaptive cultural local practices and knowledge, which have made them more resilient in the face of disasters.

These subsistence practices especially helped rural Pacific Island communities cope through the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. While many Pacific Island governments thwarted community transmission of the virus by closing international borders and imposing restrictions on movement, these same measures created hardships through employment losses and supply chain disruptions.

In our recent study published in the journal Marine Policy and led by partners within Teri Tuxson’s organization, the Locally Managed Marine Area Network, we found that despite early concerns, Pacific Island communities across seven countries—Papua New Guinea, Palau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Fiji, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Solomon Islands—remained relatively resilient through 2020, when some of the worst effects of the pandemic were being felt around the world. That’s because they were able to fall back on existing customs of food sharing and on their knowledge of food production techniques to ensure food availability during this period.

Strong social networks among Pacific Islanders have long fostered resilience to food system shocks, both within and between island communities. Historically, relationships built during ceremonial trade between islanders had the additional purpose of helping these communities to obtain or barter for goods needed during times of crop failure or disasters.

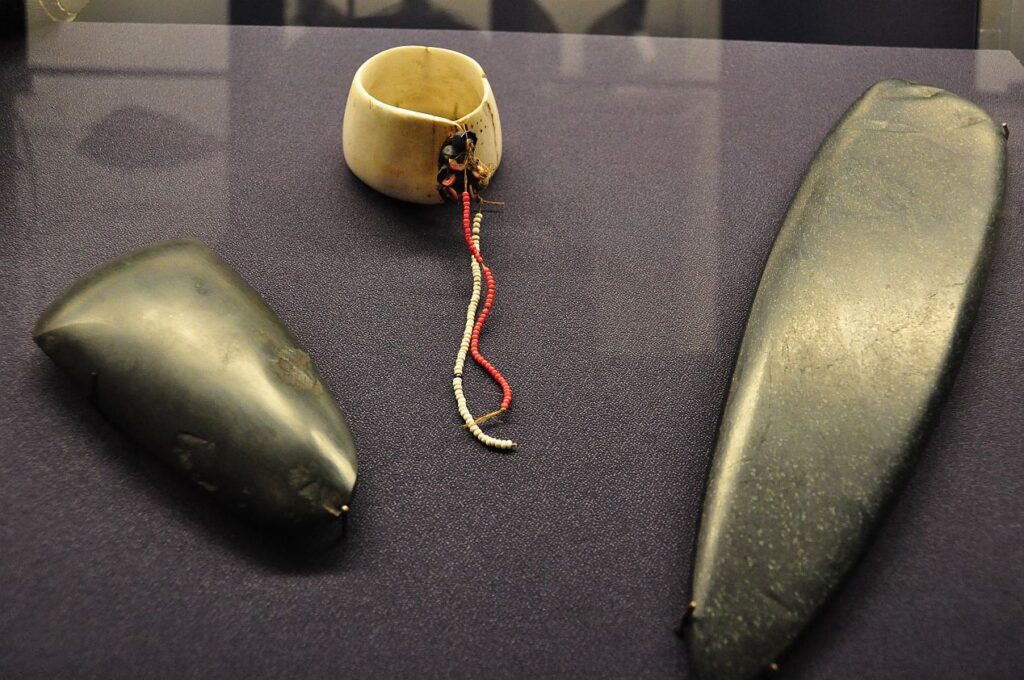

One excellent example of this is the Kula ring, first described in 1922 by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski in his tome, Argonauts of the Western Pacific. The Kula ring refers to a traditional trade alliance joining communities of east New Guinea. The main purpose of the Kula ring was to reciprocally exchange two goods with local symbolic value—long, red shell necklaces called soulava were traded for white shell bracelets called mwali.

Through this trade, other ordinary goods such as food items were also exchanged on the side, which solidified lasting relationships between groups that could provide assistance to each other to recover from disasters.

This type of food sharing ensured survival in these communities. In addition to trade alliances, other strategies promoted resilience via bet-hedging. Examples of this include crop diversification; surplus food production, preservation and storage; maintenance of tenure boundaries (land or sea areas over which kinship groups control access and use of natural resources); and cooperation among family groups and clans under traditional governance hierarchies. Many of these practices are still in place today and are visible in communities that have been best able to weather impacts from natural disasters and sudden shocks.

For example, Tropical Cyclone Ofa hit Samoa in 1990. Although important cash crops such as coconut were severely affected during the cyclone, local communities maintained resilience through community cooperation and cohesiveness, including through food exchange. In some cases, village chiefs instructed farmers to plant fast-growing crops on available communal lands. Meanwhile, several villages revived the fading practice of pit fermentation of breadfruit immediately following the cyclones to maintain a steady food supply.

While carrying out surveys for the Marine Policy report, we also found that rural communities in Papua New Guinea who were simultaneously affected in 2020 by both the pandemic hardships and a severe drought turned to bartering for goods between communities and relying on sago palm production to supplement agricultural activities.

One man from Palau who responded to our survey noted, “It is part of our culture to share food with others,” adding that he and other fishermen “started sharing more than we normally do because we couldn’t sell our catch, especially when COVID-19 started, and there were no tourists coming.”

In Fiji, where many villages were battered by Tropical Cyclone Harold in early April 2020 just before the government imposed pandemic-related travel restrictions, a female respondent reported that, “Some farms were affected during the cyclone and, on top of that, we couldn’t go to town to buy groceries because of travel restrictions. So, we were depending on seafood.”

These sentiments were heard consistently across the Pacific, where rural residents fell back on their knowledge of salting fish, tending taro patches, and using ancestral techniques and methods handed down by previous generations.

Disasters in the Pacific region are inevitable. The eruption on January 15 of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano, with more power than an atomic bomb, created a tsunami that was felt as far away as Japan and California. Moreover, it had a devastating impact on infrastructure in the low-lying islands of Tonga and destroyed crops through ash fall.

But the signs of resilience are already showing. Tongan communities around Oceania have galvanized to organize shipments of food supplies and aid—demonstrating the strength of social networks that can be nearly instantaneously activated. In the weeks and months ahead, customs of food sharing and knowledge of food preservation will most certainly be put to use to get communities through this time of hardship.

A version of this article first appeared on Truthout and was produced in partnership with Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

###

Stacy Jupiter is a 2019 MacArthur Fellow and the Melanesia regional director with the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Teri Tuxson is the assistant coordinator of the Locally Managed Marine Area Network.

Caroline Ferguson is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Sangeeta Mangubhai is a 2018 Pew marine fellow with Talanoa Consulting.

Take action…

President Biden: Declare a climate emergency

“Climate change is here, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. The recent Supreme Court decision limiting the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to regulate coal- and gas-fired power plants makes it abundantly clear that President Biden must declare a climate emergency,” says the Center for Biological Diversity.

“Officially declaring the climate crisis a national emergency would unlock the tools needed to steer the economy away from fossil-fueled climate catastrophe toward a sustainable, just future. Biden needs to hear from you.”

Urge President Biden to finally declare a climate emergency.

ICYMI…

The Human Mania for Roadbuilding Is a Threat to the Great Apex Predator Species

By Jeffrey Dunnink, Independent Media Institute

Designed for speed and efficiency, roadways across the globe are effectively killing wildlife whose futures are intrinsically linked to the future of the planet: apex predators, those species including big cats like tigers and leopards who sit at the top of the food chain and ensure the health of all biodiversity.

A new study I coauthored confirms that apex predators in Asia currently face the greatest threat from roads, likely due to the region’s high road density and the numerous apex predators found there. Eight out of the 10 species most impacted by roads were found in Asia, with the sloth bear, tiger, dhole, Asiatic black bear and clouded leopard leading the list.

The outlook for the next 30 years is even more dire. More than 90 percent of the 25 million kilometers of new global road construction expected between now and 2050 will be built in developing nations that host critical ecosystems and rich biodiversity areas. Proposed road developments across Africa, the Brazilian Amazon and Nepal are expected to intersect roughly 500 protected areas. This development directly threatens the core habitats of apex predators found in these regions and will potentially disrupt the functioning and stability of their ecosystems. This is particularly concerning where road developments will impact areas of rich biodiversity and where conservation gains have been so painstakingly achieved.

Parting thought…

“Ethical veganism results in a profound revolution within the individual; a complete rejection of the paradigm of oppression and violence that she has been taught from childhood to accept as the natural order. It changes her life and the lives of those with whom she shares this vision of nonviolence. Ethical veganism is anything but passive; on the contrary, it is the active refusal to cooperate with injustice.” —Gary L. Francione

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.