A scientist went against the grain on her industry’s rule against anthropomorphizing nonhuman animals—here’s what she discovered.

By Catherine Raven, Independent Media Institute

8 min read

This excerpt is from Fox & I: An Uncommon Friendship by Catherine Raven. Copyright © 2021 by the author and reprinted with permission of Spiegel & Grau, LLC. It was adapted for the web by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Editor’s note: At 15, Catherine Raven left home and headed west to work as a national park ranger. She later earned a PhD in biology and built an off-the-grid house on an isolated plot of land in Montana, making a living by remote teaching and leading field classes in Yellowstone National Park. One day, she noticed that the wild fox who had been showing up on her property was now appearing every day at 4:15 p.m. One day she brought a camping chair outside and sat just feet away from him. And then she began to read to him from The Little Prince. Her memoir about the relationship that developed between them, Fox & I: An Uncommon Friendship, is the winner of the 2022 PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award.

For 12 consecutive days, the fox had appeared at my cottage. At no more than one minute after the sun capped the western hill, he lay down in a spot of dirt among the powdery blue bunchgrasses. Tucking the tip of his tail under his chin and squinting his eyes, he pretended to sleep. I sat on a camp chair with stiff spikes of bunchgrass poking into the canvas. Opening a book, I pretended to read. Nothing but 2 meters and one spindly forget-me-not lay between us. Someone may have been watching us—a dusky shrew, a field mouse, a rubber boa—but it felt like we were alone with the world to ourselves.

On the thirteenth day, at around 3:30 and no later than 4 p.m., I bundled up in more clothing than necessary to stay comfortably warm and went outside. Pressing my hands together as if praying, I pushed them between my knees while I sat with my feet tapping the ground. I was waiting for the fox and hoping he wouldn’t show.

Two miles up a gravel road in an isolated mountain valley and 60 miles from the nearest city, the cottage was not an appropriate arrangement for a girl on her own. My street was unnamed, so I didn’t have an address. Living in this remote spot left me without access to reasonable employment. I was many miles beyond reach of cell phone towers, and if a rattlesnake bit me, or if I slipped climbing the rocky cliff behind the cottage, no one would hear me cry for help. Of course, this saved me the trouble of crying in the first place.

I had purchased this land three years earlier. Until then I had been living up valley, renting a cabin that the owner had “winterized,” in the sense that if I wore a down parka and mukluks to bed, I wouldn’t succumb to frostbite overnight. That was what I could afford with the money I’d earned guiding backcountry hikers and teaching field classes part-time. When a university offered me a one-year research position, you might think I would have jumped at the chance to leave. Not just because I was dodging icicles when entering the shower, but because riding the postdoc train was the next logical step for a biologist. But I didn’t jump. I made the university wait until after I had bought this land. Then I accepted and rented a speck of a dormitory room at the university, 130 miles away. Every weekend, through snowstorms and over icy roads, I drove back here to camp. Perching on a small boulder, listening to my propane stove hissing and the pinging sound of grasshoppers flying headfirst into my tent’s taut surface, I felt like I was part of my land. I had never felt part of anything before. When the university position ended, I camped full-time while arranging for contractors to develop the land and build the cottage.

Outside the cottage, from where I sat waiting for the fox, the view was beautiful. Few structures marred my valley; full rainbows were common. The ends of the rainbows touched down in the rolling fields below me, no place green enough to hide a leprechaun but a fair swap for living with rattlers. Still, I was torn. Even a full double rainbow couldn’t give me what a city could: a chance to interact with people, immerse myself in culture, and find a real job to keep me so busy doing responsible work that I wouldn’t have time for chasing a fox down a hole. I had sacrificed plenty to earn my PhD in biology: I had slept in abandoned buildings and mopped floors at the university. In exchange for which I had learned that the scientific method is the foundation for knowledge and that wild foxes do not have personalities.

When Fox padded toward me, a flute was playing a faint, hypnotic melody like the Pied Piper’s song in my favorite fairy tale. You remember: a colorfully dressed stranger appears in town, enticing children with his music to a land of alpine lakes and snowy peaks. When the fox curled up beside me and squinted, I opened my book. The music was still playing. No, it wasn’t the Pied Piper at all. It was just a bird—a faraway thrush.

…

The next day, while waiting for Fox’s 4:15 appearance, I thought about our upcoming milestone: 15 consecutive days spent reading together—six months in fox time. Many foxes had visited before him; some had been born a minute’s walk from my back door. All of them remained furtive. Against all odds, and over several months, Fox and I had created a relationship by carefully navigating a series of sundry and haphazard events. We had achieved something worth celebrating. But how to celebrate?

I decided to ditch him.

I poured coffee grounds from a red can into a pot of boiling water, waited to decant cowboy coffee, and thought about how to lose the fox. Maybe he wouldn’t come by anymore. I opened the door of the fridge. “Have I mistaken a coincidence for a commitment?”

The refrigerator had no answer and very little food. But it gave me an idea. I drew up a list of grocery items and enough chores to keep me busy until long after 4:15 p.m. and headed out. The supermarket was in a small town thirty miles down valley, and I had to drive with my blue southern sky behind me. Ahead, black-bottomed clouds with white faces chased each other into the eastern mountains. Below, in the revolving shade, Angus cattle, lambing ewes, and rough horses conspired to render each passing mile indistinguishable from the one before. Usually, I tracked my location counting bends in the snaky river, my time watching the clouds shift, and my fortune spotting golden eagles. (Seven was my record; four earned a journal entry.) Not today.

Now that I was free to be anywhere I wanted at 4:15 p.m., I returned to my mercurial habits and drove too fast to tally eagles. Imagine a straight open road with no potholes and not another rig in sight. Shifting into fifth gear, I straddled the centerline to correct the bevel toward the borrow pit and accelerated into triple digits. Never mind the adjective, I was mercury: quicksilver, Hg, hydrargyrum, ore of cinnabar, resistant to herding, incapable of assuming a fixed form. The steering wheel vibrated in agreement.

The privilege of consorting with a fox cost more than I had already paid. The previous week, while I was in town collecting my groceries, I got a wild hair to stop at the gym. The only person lifting weights was Bill, a scientist whom I had worked with in the park service. I mentioned that a fox “might” be visiting me. “As long as you’re not anthropomorphizing,” he responded. Six words and a wink left me mortified, and I slunk away. Anthropomorphism describes the unacceptable act of humanizing animals, imagining that they have qualities only people should have, and admitting foxes into your social circle. Anyone could get away with humanizing animals they owned—horses, hawks, or even leashed skunks. But for someone like me, teaching natural history, anthropomorphizing wild animals was corny and very uncool.

You don’t need much imagination to see that society has bulldozed a gorge between humans and wild, unboxed animals, and it’s far too wide and deep for anyone who isn’t foolhardy to risk the crossing. As for making yourself unpopular, you might as well show up to a university lecture wearing Christopher Robin shorts and white bobby socks as be accused of anthropomorphism. Only Winnie-the-Pooh would associate with you.

Why suffer such humiliation? Better to stay on your own side of the gorge. As for me, I was bushed from climbing in, crossing over, and climbing out so many times. Sometimes, I wasn’t climbing in and out so much as falling. Was I imagining Fox’s personality? My notion of anthropomorphism kept changing as I spent time with him. At this point, at the beginning of our relationship, I was mostly overcome with curiosity.

Catherine Raven is a former national park ranger at Glacier, Mount Rainier, North Cascades, Voyageurs, and Yellowstone national parks. She earned a PhD in biology from Montana State University, holds degrees in zoology and botany from the University of Montana, and is a member of American Mensa and Sigma Xi. Her natural history essays have appeared in American Scientist, Mensa Journal, and Montana Magazine.

Take action…

Protect wild foxes in the United Kingdom from illegal hunting

Keep the Ban: “At least 84 percent of the U.K. population are in favor of fox hunting being illegal and yet there were attempts to weaken the act. The Hunting Act of 2004, which banned fox hunting, needs strengthening to ensure people are discouraged from participating in illegal hunting, and for those caught hunting, the penalty and arrest need to be more severe. We would like to see section 6 of the Act to be amended to add a provision for a prison sentence of up to six months for illegal hunting. Additionally, there should be a ‘reckless’ clause that will make it an offense for anyone to ‘cause or permit’ one or more dogs to seek out, chase, injure or kill a wild mammal. The widespread flouting of the ban continues to this day and these measures along with several other reforms could ensure wildlife is adequately protected.”

Urge U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson to strengthen the 2004 Hunting Act to protect wild foxes.

Cause for concern…

The collapse of a major Atlantic current would cause worldwide disasters

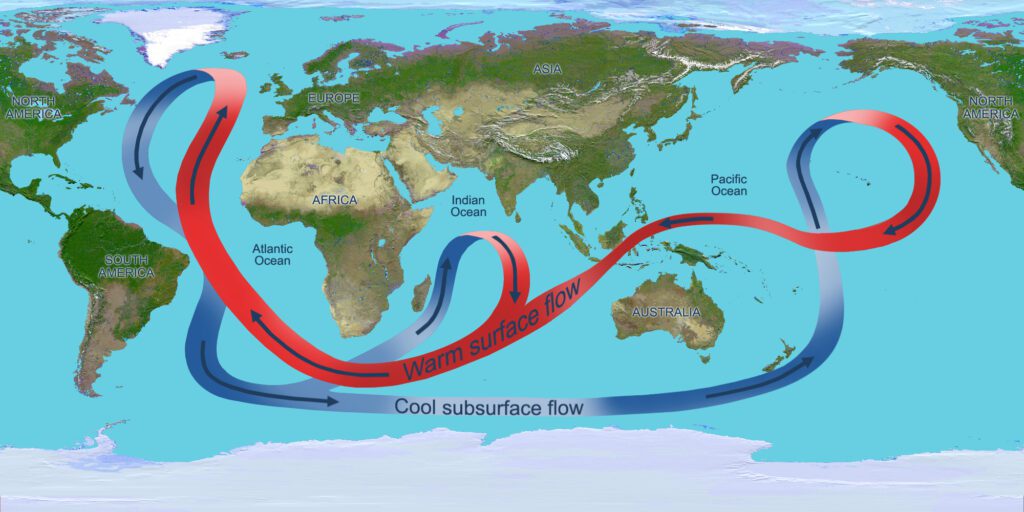

“A shutdown of a major current in the Atlantic Ocean would rapidly transform wind, temperature, and precipitation patterns across the whole globe, according to new research,” reports Lauren Leffer for Gizmodo. “The current is already slowing, likely at least in part because of human-caused climate change. Now, scientists have found that, if the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) collapses completely, there would be never-before-predicted impacts, according to a study published last week in the journal Nature Climate Change.”

“The northern Pacific Ocean would cool. Patches of the Northern Hemisphere would get drier, while patches of the South become wetter,” writes Leffer. “Atmospheric pressure would shift to be much higher over Eurasia and other parts of the Northern Hemisphere. Trade winds from the north would move farther south and get stronger. Other winds elsewhere would also intensify. Antarctic ice could melt even faster. In short: all the basics about the planet we know and love get thrown way out of whack. No corner of Earth is forecast to be unaffected by an AMOC collapse in the new research.”

Letter to the editor…

Dear Earth | Food | Life,

Last week, thanks to the Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts and the Santa Barbara County Food Action Network, I was able to join the Santa Barbara Culinary Experience. There, I had the honor of speaking with Congressmember Salud Carbajal, truly one of the food and labor warriors in Congress who’s working across party lines to help farmers, workers, and eaters alike.

Whether or not the politicians we voted for are the ones who end up representing us, he said that the communication between citizens and our elected officials is vital. Rep. Carbajal told me that the stories he hears from his constituents really matter, and he takes them seriously. A lot of folks might think it’s old-fashioned to write, email, or call your representatives, senators, and governors, but it really makes a difference. Do it right now—here’s a link to contact your elected officials.

And like many of us in the food system, Rep. Carbajal has also been devoting energy and thought to the Farm Bill. Yes, it’s a messy and complicated piece of legislation. It also holds massive potential to really help farmers, eaters, and businesses in the food and agriculture sectors to do things differently. One place to start is by incorporating food security and food sovereignty more strongly into the Farm Bill. I’m invigorated by an idea I’ve heard from Ricardo Salvador of the Union of Concerned Scientists, chef Andrew Zimmern, and others: A coordinated national food policy, or even a Secretary of Food or a Food and Farm Bill to unify our national and international approaches to food.

Dani Nierenberg

President

Food Tank

May 26, 2022

ICYMI…

Thinking about chickens differently

Though chickens are polygamous, mating with more than one member of the opposite sex, individual birds are attracted to each other. They not only “breed”; but they also form bonds, clucking endearments to one another throughout the day. A rooster does a courtly dance for his special hens in which he “skitters sideways and opens his wing feathers downward like Japanese fans,” according to Rick and Gail Luttmann’s book “Chickens in Your Backyard.” A man once told me, “When I was a young man I worked on a chicken farm, and one of the most amazing things about those chickens was that they would actually choose each other and refuse to mate with anyone else.”

Sadly, the eggs of these parent flocks are snatched away and sent to mechanical incubators, so the parents never see their chicks. “Breeder” roosters and hens are routinely culled for low fertility, and also because “if a particular male becomes unable to mate, his matching females will not accept another male until he is removed,” explains the book “Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg Production.”

Little more than a year later, the parents who have survived their miserable life are sent to slaughter just like the chicks they never got to see, raise or protect, as they would otherwise have chosen to do if they were free.

—EFL contributor Karen Davis, “On International Respect for Chickens Day, Try Thinking About Them Differently” (Countercurrents, April 26, 2022)

Parting thought…

“Just how destructive does a culinary preference have to be before we decide to eat something else? If contributing to the suffering of billions of animals that live miserable lives and (quite often) die in horrific ways isn’t motivating, what would be? If being the number one contributor to the most serious threat facing the planet (global warming) isn’t enough, what is? And if you are tempted to put off these questions of conscience, to say not now, then when?” —Jonathan Safran Foer, “Eating Animals”

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.