Chickens deserve our respect.

By Karen Davis, Independent Media Institute

6 min read

“I hear the universal cock-crowing with surprise and pleasure, as if I never heard it before. What a tough fellow! How native to the earth!” —Henry David Thoreau

Chickens are indeed native to the earth. Despite centuries of domestication—from the tropical forest to the farmyard to the factory farm—the call of the wild has always been in the chicken’s heart. Far from being “chicken,” roosters and hens are legendary for their bravery. In classical times, the bearing of the rooster—the old British term for “cock,” a word that was considered too sexually charged for American usage—symbolized military valor: the rooster’s crest stood for the soldier’s helmet and his spurs stood for the sword. A chicken will stand up to an adult human being. Our tiny Bantam rooster, Bantu, would flash out of the bushes and repeatedly attack our legs, lest we should disturb his beloved hens. (Although we do not allow our chickens to hatch chicks, in 2018 a hen and a rooster rescued from a cockfighting operation produced a surprise family, the hen having camouflaged herself in a wooded area of our sanctuary.)

An annoyed hen will confront a pesky young rooster with her hackles raised and run him off. Although chickens will fight fiercely, and sometimes successfully, with foxes and other predators to protect their families, with humans, however, this kind of bravery usually does not win. A woman employed on a chicken “breeder” farm in Maryland, berated the defenders of chickens for trying to make her lose her job, and threatening her ability to support herself and her daughter. For her, the “breeder” hens were “mean” birds who “peck your arm when you are trying to collect the eggs.” In her defense for her life and her daughter’s life, she failed to see the similarity between her motherly protection of her child and the exploited hen’s courageous effort to protect her own offspring.

In an outdoor chicken flock, similar to the 12,000 square feet, predator-proof sanctuary my organization United Poultry Concerns has in rural Virginia, ritual and playful sparring and chasing normally suffice to maintain peace and resolve disputes among chickens without bloodshed. Even hens will occasionally have a spat, growling and jumping at each other with their hackles raised; but in more than 30 years of keeping chickens, I have never seen a hen fight turn seriously violent or last for more than a few minutes. Chickens have a natural instinct for social equilibrium and learn quickly from each other. An exasperated bird will either move away from the offender or aim a peck, or a pecking gesture, which sends the message: “Back off.”

Bloody battles, which usually take place when a new rooster is introduced into an established flock, are rare, short-lived and usually affect the comb—the crest on top of a chicken’s head—which, being packed with blood vessels, can make an injury look worse than it usually is. It is when chickens are crowded, confined, frustrated or forced to compete at a feeder that distempered behavior can erupt. By contrast, chickens allowed to grow up in successive generations, unconfined in buildings, do not evince a rigid “pecking order.” Parents oversee their young, and the young contend playfully, and indulge in many other activities. A flock of well-acquainted chickens is an amiable social group.

Sometimes chickens run away, however, fleeing from a bully or hereditary predator on legs designed for the purpose does not constitute cowardice. At the same time, I’ve learned from painful experience how a rooster who rushes in to defend his hens from a fox or a raccoon usually does not survive the encounter.

Though chickens are polygamous, mating with more than one member of the opposite sex, individual birds are attracted to each other. They not only “breed”; but they also form bonds, clucking endearments to one another throughout the day. A rooster does a courtly dance for his special hens in which he “skitters sideways and opens his wing feathers downward like Japanese fans,” according to Rick and Gail Luttmann’s book, Chickens in Your Backyard. A man once told me, “When I was a young man I worked on a chicken farm, and one of the most amazing things about those chickens was that they would actually choose each other and refuse to mate with anyone else.”

Sadly, the eggs of these parent flocks are snatched away and sent to mechanical incubators, so the parents never see their chicks. “Breeder” roosters and hens are routinely culled for low fertility, and also because “if a particular male becomes unable to mate, his matching females will not accept another male until he is removed,” explains the book Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg Production.

Little more than a year later, the parents who have survived their miserable life are sent to slaughter just like the chicks they never got to see, raise or protect, as they would otherwise have chosen to do if they were free.

To afford this chance for chickens to live a cage-free life along with their chicks, we should show compassion to chickens in May in honor of International Respect for Chickens Day, which falls on May 4, 2022. Most of all, we need to respect the lives of chickens beyond this day by ensuring that chickens are treated humanely, and by making better food choices, which involves a shift away from a meat-based diet toward a plant-based diet.

###

Karen Davis, PhD, is the president and founder of United Poultry Concerns, a nonprofit organization that promotes the compassionate and respectful treatment of domestic fowl including a sanctuary for chickens in Virginia. Davis is an award-winning animal rights activist and the author of numerous books, including a children’s book (A Home for Henny); a cookbook (Instead of Chicken, Instead of Turkey); Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs; More Than a Meal; and her latest book, a series of essays called For the Birds.

Take action…

“Today, chickens are bred to grow four times faster and considerably larger than in the 1950s, when industrial chicken production was just beginning. In the span of just 48 days—a tiny fraction of their natural lifespan—baby chickens reach a gargantuan size. The issue is so severe that if humans grew at a rate similar to McDonald’s chickens, we would weigh 660 pounds at just two months old,” writes EFL contributor Taylor Ford of The Humane League in Truthout.

“This rapid growth makes it difficult, and sometimes impossible, for many chickens to walk. Additionally, these chickens are constrained to overcrowded, dark, unnatural and barren barns, causing painful conditions, including horrifying ammonia burns on their chest and legs from the waste and sickness permeating the space. These are the brutal conditions that make up the tens of millions of chickens’ lives in McDonald’s supply chain.”

Urge McDonald’s to stop using chickens who are bred to suffer.

Cause for concern…

Over 137 million Americans live in areas with poor air quality

“Despite decades of environmental efforts, over 40 percent of Americans—more than 137 million people—live in cities and states with poor air quality, a new report says,” writes Dustin Jones for NPR. “And, in addition to cars and factories, wildfires are increasingly contributing to unhealthy air.”

Round of applause…

Biden order aims to protect old-growth forests from wildfire

“President Joe Biden is taking steps to restore national forests that have been devastated by wildfires, drought and blight, using an Earth Day visit to Seattle to sign an executive order protecting some of the nation’s largest and oldest trees,” report Matthew Daly and Josh Boak report for the Associated Press.

ICYMI…

Geoengineering: Climate cure or climate concern?

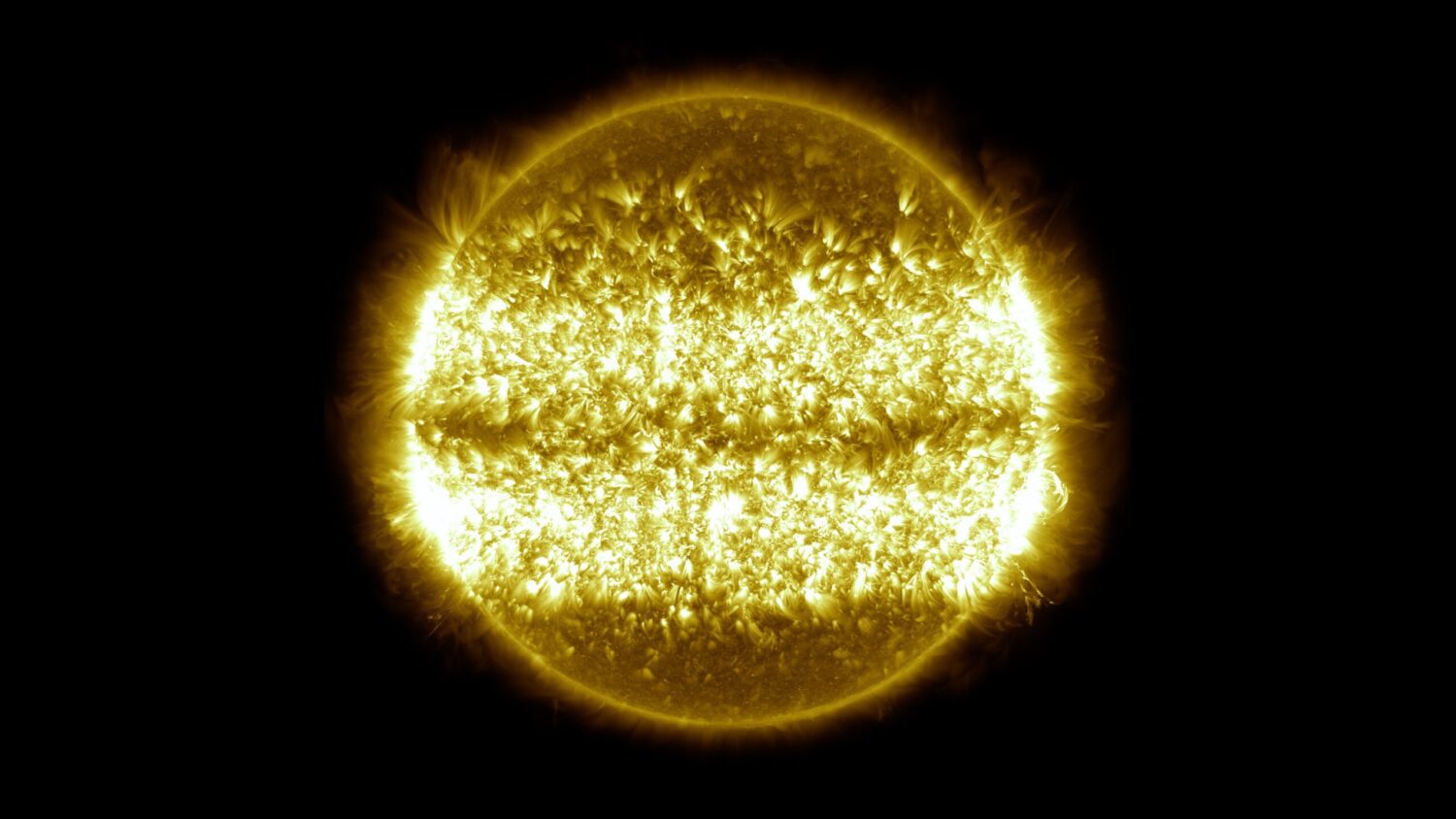

“As scientists, policymakers and politicians keep one increasingly startled eye on climate change’s ticking clock and the other on the ongoing, upwardly mobile trend in greenhouse gas emissions, it’s no wonder possible solutions that have been long dismissed as fringe slices of science fiction are making their way into the mainstream. Enter center stage geoengineering, a hitherto black sheep of the fight against global warming.

“[T]echnologies under the rubric of solar radiation management (SRM) are expected to work on a much faster timescale, and as a consequence, generate arguably the greater buzz. Solar engineering is the idea that humankind artificially limits how much sunlight and heat are permitted in the atmosphere, and includes the thinning of high-level cirrus clouds to help infrared rays more easily escape upward, along with the brightening of low-level marine clouds to help reflect sunlight back into space.”

—EFL contributor Daniel Ross, “Should Humans Try to Modify the Amount of Sunlight the Earth Receives?” (NationofChange, November 10, 2021)

Parting thought…

“[P]erhaps now more than ever, is time for us, as a collective, to decide what environmental consciousness means and looks like to us, for it’s clear we’ve become disconnected from the life force energy that binds us to our environment.” —Zaria Howell, “Nature as Healing” (Currently, April 24, 2022)

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.