Econo-diversity makes cities resilient in times of crisis.

By Christina Conklin and Marina Psaros

6 min read

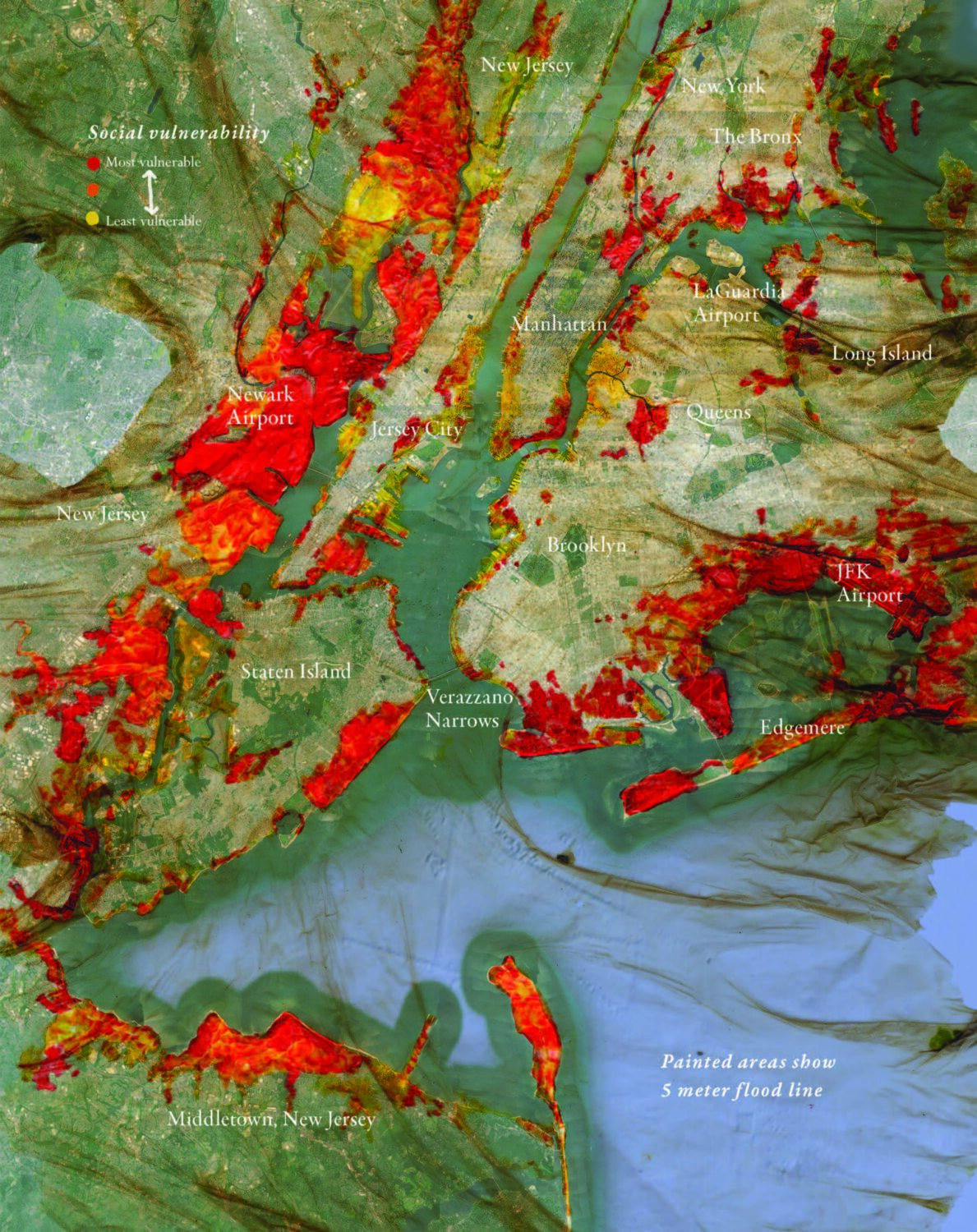

Editor’s note: Using a unique blend of place-based storytelling and clear explanations of both climate science and climate policy, Christina Conklin and Marina Psaros, in their new bookThe Atlas of Disappearing Places: Our Coasts and Oceans in the Climate Crisis(2021, The New Press), look at the likely impacts of the climate crisis—extreme weather, melting sea ice, flooded coastlines, and species extinction in 20 of the most at-risk communities around the globe, from New York, Shanghai and the Cook Islands, to Bangladesh, Kenya and Vietnam.

© 2021 Christina Conklin and Marina Psaros. This excerpt, adapted for the web, originally appeared in The Atlas of Disappearing Places: Our Coasts and Oceans in the Climate Crisis, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

The 2020s were lean years in New York, as elsewhere. But the city’s 2022 lawsuit against the Big Five—Chevron, BP, Shell, Exxon, and ConocoPhillips—picked up where their 2018 lawsuit had failed, seeking to defray the skyrocketing costs of climate adaptation. Dozens of other cities, counties, and states had also taken legal action, chipping away at the oil companies’ deniability defense until it was clear the oil giants had known for decades they were deceiving the public about their direct responsibility for global warming. Investor unease forced them to ask the State Department to facilitate a grand settlement. By 2026, the Greenhouse Gas Settlement’s trust fund received its opening payments of $100 billion, a sum to be paid annually for as long as each company earned revenue through fossil fuel extraction. This sudden disincentive to produce catalyzed the U.S. energy industry’s first real commitment to renewables, far behind their Asian and OPEC counterparts.

New York used its share of the settlement to channelize the streets in Lower Manhattan, making them concave rather than convex—a Danish idea that successfully drained most water away from subway entrances. The city levied a graduated carbon tax that allowed developers and billionaires to pick up most of the tab for improved sea defenses along with tax credits to those who included more than 50 percent affordable housing on land higher than three meters (ten feet) above the 2020 sea level. Mostly, citizens and leaders carried on as they always had, aware of the need for action but not willing to give up the familiar contours of their city.

But the Valentine’s Day Flood of 2033 changed the public’s understanding of just how dangerous a storm could be. Rather than a sea surge like Sandy, this unseasonably warm nor’easter blew in heavy rains from upstate, sending more than 6 centimeters (2.5 inches) of water per hour down rivers, streets, and subway tunnels every hour. February’s full moon brought the highest tides of the year into New York Harbor, sending water deep into Bronx and Queens neighborhoods that had never seen flooding before. Many who were out for the night did not receive the text alerts, and nearly 20,000 people drowned as roads became rivers.

The rain came down for four days and nights. Much of the region’s transportation system was shut down for months. Half a million people fled upstate and out of state and thousands without the means to relocate moved into makeshift shelters to wait for the cleanup. The lesson of Sandy—that far-sighted relocation planning could prevent much suffering—hadn’t been learned. The city had no comprehensive flood response plan in place, and many flood barriers had failed, so slow recovery response heaped layers of trauma onto a city that had already been through so much.

But some communities on Staten Island, which had a lot of experience with flooding, had been prepared. They had held community meetings since Sandy, where they discussed and debated different approaches to coping with the Big One they all knew was coming. When it did, they felt clear-eyed, informed, and self-empowered. Their block-by-block safety teams helped the elderly and disabled evacuate to agreed safe houses, and the rest headed for the well-appointed shelter they had campaigned for a decade earlier, built on the high ground of the former Fresh Kills landfill. The borough had the lowest death toll in the city, even though it was largely a former swamp.

New Jersey and Connecticut were also devastated, with many smaller rivers breaching their banks and washing away small towns. The three governors crossed political lines to finally implement a plan that had first been proposed back in 2017, creating a Regional Coastal Commission and vesting it with the regulatory powers to relocate low-lying communities and add protection to higher, densely populated places. After two years of thoughtful development, the commission released the New Mannahatta Plan, a vision that more closely realigned the metropolitan landscape with its original 17th-century topography. In Manhattan, Canal Street was reverted to an actual canal, and Water Street became the shoreline and a floodable park. In Staten Island and Queens, whole neighborhoods were rebuilt further inland, the buildings torn down and converted into storm berms along the +2-meter shoreline. All along the tri-state coast, the RCC established floating communities, added ferries and water taxis, converted the most undefendable sites to open space, and built even denser urban hubs on high ground.

They opened Meadowlands National Park as a restored wetlands, to great fanfare. As the subway faltered and failed after repeated inundations, the city re-elevated its trains, running them up the dry spine of Manhattan from the Bowery to Broadway and Central Park. Transformational adaptation had finally reached the shores of the Hudson.

It took more than two decades to fully implement, but as the city enters the second half of the century, it has squarely faced its challenging geography. Now, New York is indeed the “dramatically reshaped city” that Daniel Zarrilli, former chief climate policy adviser to New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, predicted decades ago, though its resilience is tinged with notes of sadness, healing, and regret.

Key Term: Economy

Economy once referred to the administration of a single home or community resources, with an emphasis on frugality. The contemporary understanding of “the economy” as a unifying national discourse only dates to the Great Depression, when countries were together by hardship. In recent generations, most nations have accepted the maxim that economic growth is the goal of a successful society. But climate instability is already creating economic instability as disasters mount, and diverse economic models are needed to see us through. Environmental economics is favored by some because it seeks to value the air, water, and land in the current system as costs and benefits are calculated. More radically, steady-state economics, first proposed by John Stuart Mill and developed more recently by Herman Daly as “ecological economics,” imagines an economy that neither grows nor shrinks, but lives within the carrying capacity of its environment, with well-distributed wealth and improving standards of living through innovation.

How we understand the purpose and goals of our economy can help us learn how to manage the finite resources of a single planet. In the United States, neighborhood barter economies, sharing economies, and local currencies all expanded in response to “shelter in place” orders that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic. Such econo-diversity (like bio-diversity) can help communities be more resilient in times of crisis.

###

Christina Conklin is an environmental artist, writer, and researcher. She is the co-author of The Atlas of Disappearing Places.

Marina Psaros is a sustainability expert and has led climate action programs across public, private, and nonprofit organizations for over a decade. She is one of the creators of the King Tides Project, an international community science and education initiative. She is the co-author of The Atlas of Disappearing Places.

Take action…

Center for Biological Diversity: “A groundbreaking report from the Center finds that 233 threatened and endangered species in 23 coastal states are at risk from sea-level rise. This means that, left unchecked, rising seas threaten the survival of 17 percent—one out of six—of our nation’s federally protected species. The report highlights five at-risk species living in different parts of our coasts: the Hawaiian monk seal, Key deer, loggerhead sea turtle, Delmarva peninsula fox squirrel, and western snowy plover. The report provides a roadmap of the priority actions needed to protect wildlife from sea-level rise impacts—foremost among them deep and rapid cuts in greenhouse gas pollution, protecting natural coastal buffers, and making room for wildlife to move inland as the oceans rise.”

Urge Congress to pass the Extinction Prevention Act to provide crucial funding for the most critically endangered species.

Cause for concern…

- New oilfield in African wilderness threatens lives of 130,000 elephants (Matthew Taylor, Guardian)

- More than a third of shark species are now threatened with extinction (Ben Panko, Smithsonian Magazine)

- Climate change could see 200 million move by 2050 (Renata Brito, Associated Press)

- Tree planting isn’t replacing burned U.S. forests—not even close (Adria Malcolm, Andrew Hay and Andrea Januta, Reuters)

Round of applause…

- Oil drilling bans advance in House with climate change assault (Jennifer A. Dlouhy, Bloomberg)

- Harvard University to end investment in fossil fuels (Ross Kerber, Reuters)

- This wildly reinvented wind turbine generates five times more energy than its competitors (Elissaveta M. Brandon, Fast Company)

- Enviros call for prompt restoration of national monuments shrunk by Trump (Zack Budryk, The Hill)

- This vegan cashew cheese is so tasty that it meets even my dairy-purist standards (Julia Pugachevsky, Business Insider)

ICYMI…

“In addition to sequestering carbon and protecting the Earth’s climate, forests provide a wide range of ecosystem services, from supplying food, fuel, timber and fiber, to purifying the air, filtering water supplies, maintaining wildlife habitats, controlling floods and preventing soil erosion. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear to the public something that scientists have been warning for decades: Deforestation is linked to the spread of zoonotic diseases. But those services are threatened when forests are cleared for wood products and land-use changes, like making space for climate-destructive industries like the meat industry.”

—EFL editor Reynard Loki, “Forests Are Crucial to Combating Climate Change—Will Biden Rise to the Challenge?” (CounterPunch, June 11, 2021)

Parting thought…

“Nature is not a place to visit. It is home.” —Gary Snyder

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.