The Heyward Shepherd memorial is an overtly pro-slavery monument erected in 1931 in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In recognition of John Brown Day, please check out an article of mine published in the Spirit of Jefferson, adapted below, about the many reasons the marker should come down.

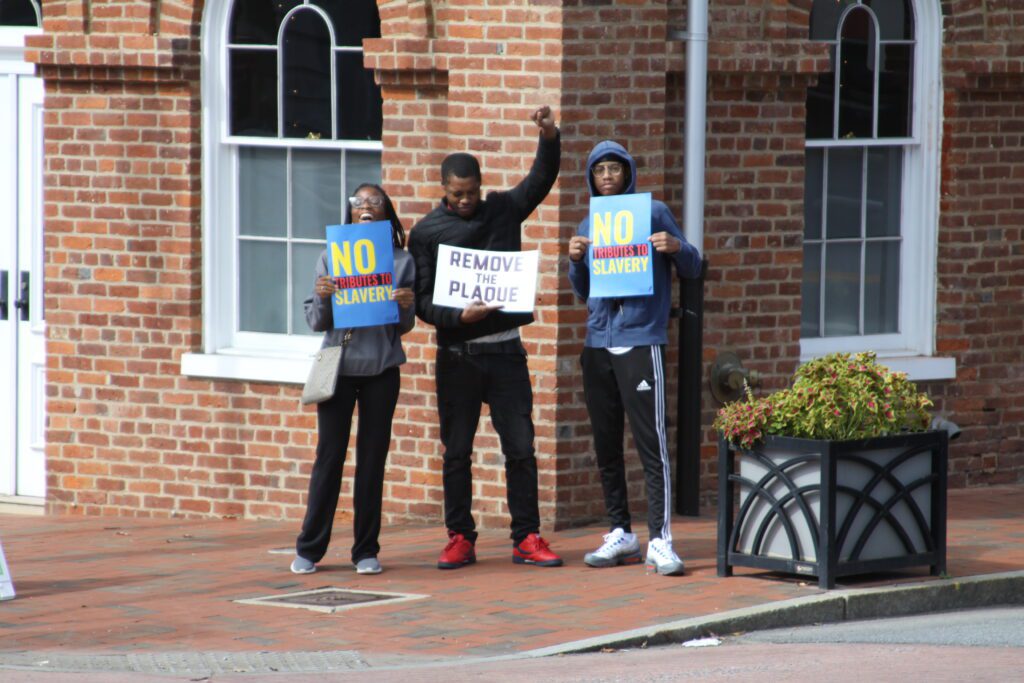

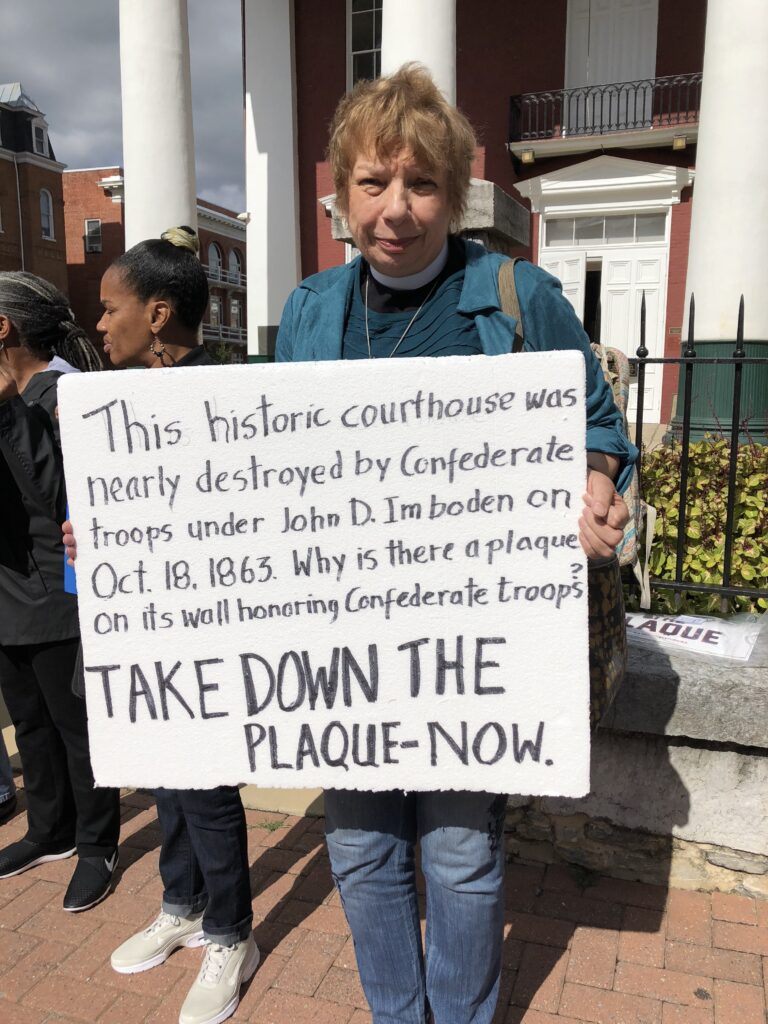

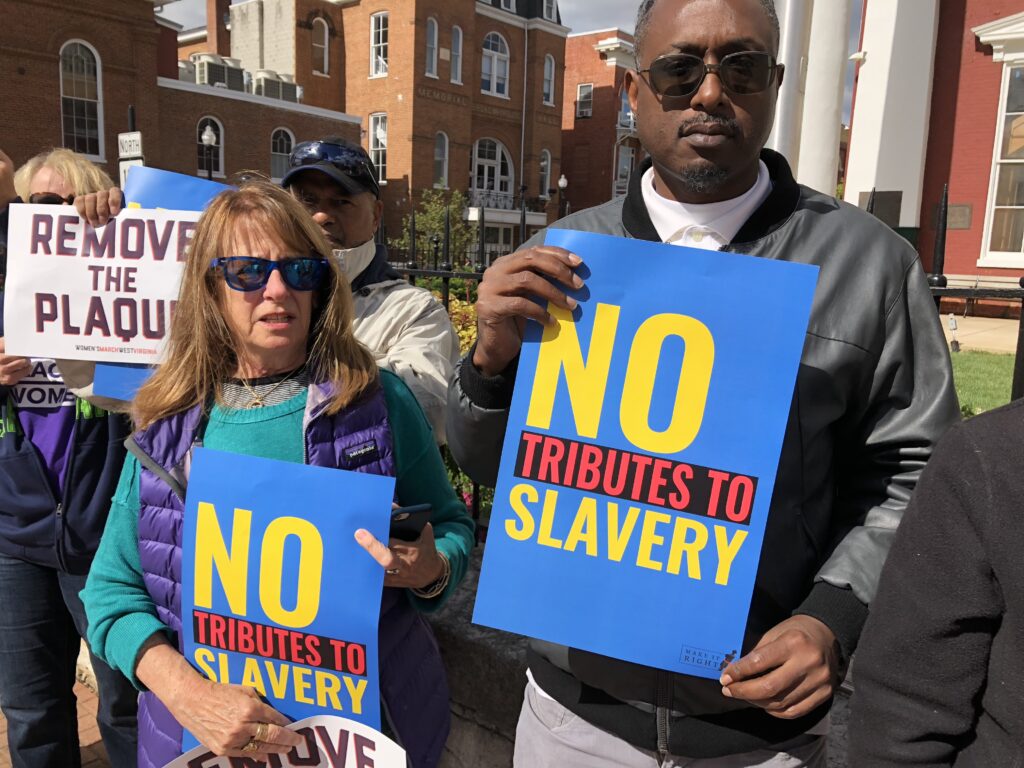

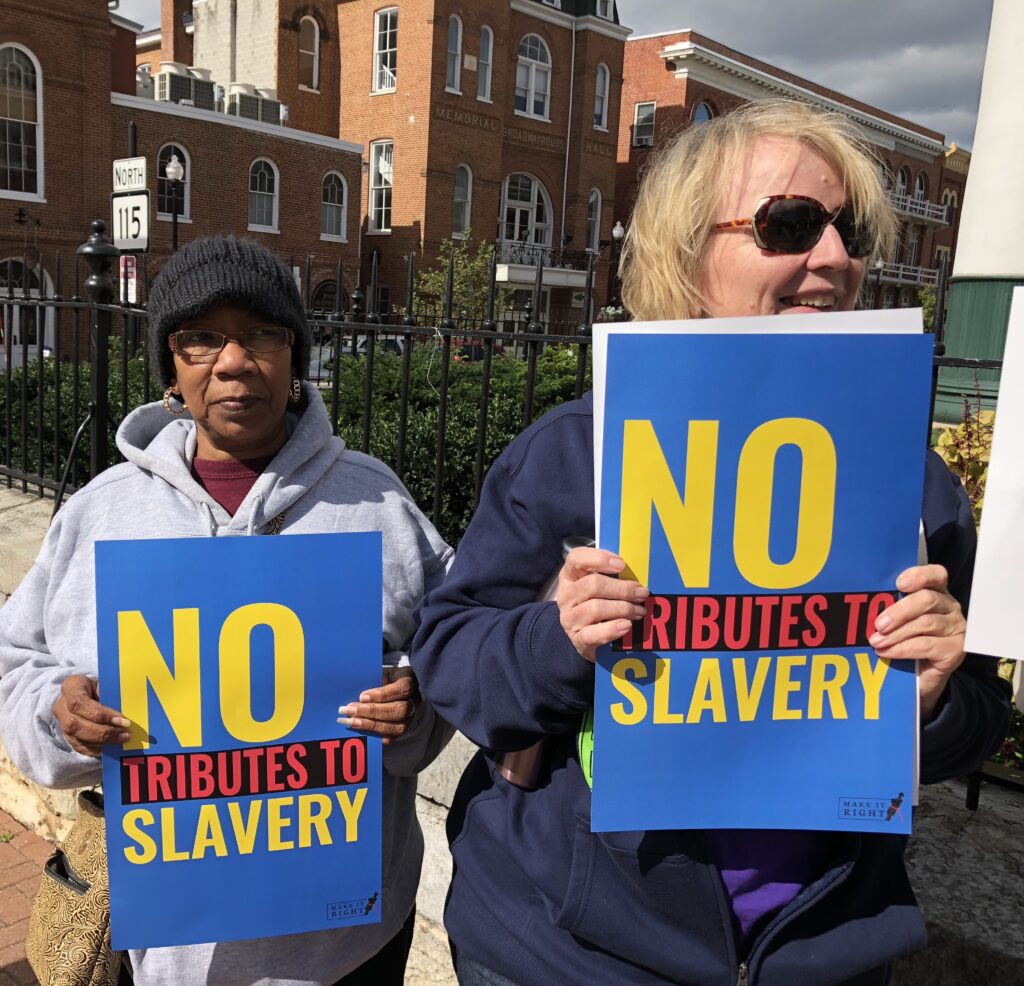

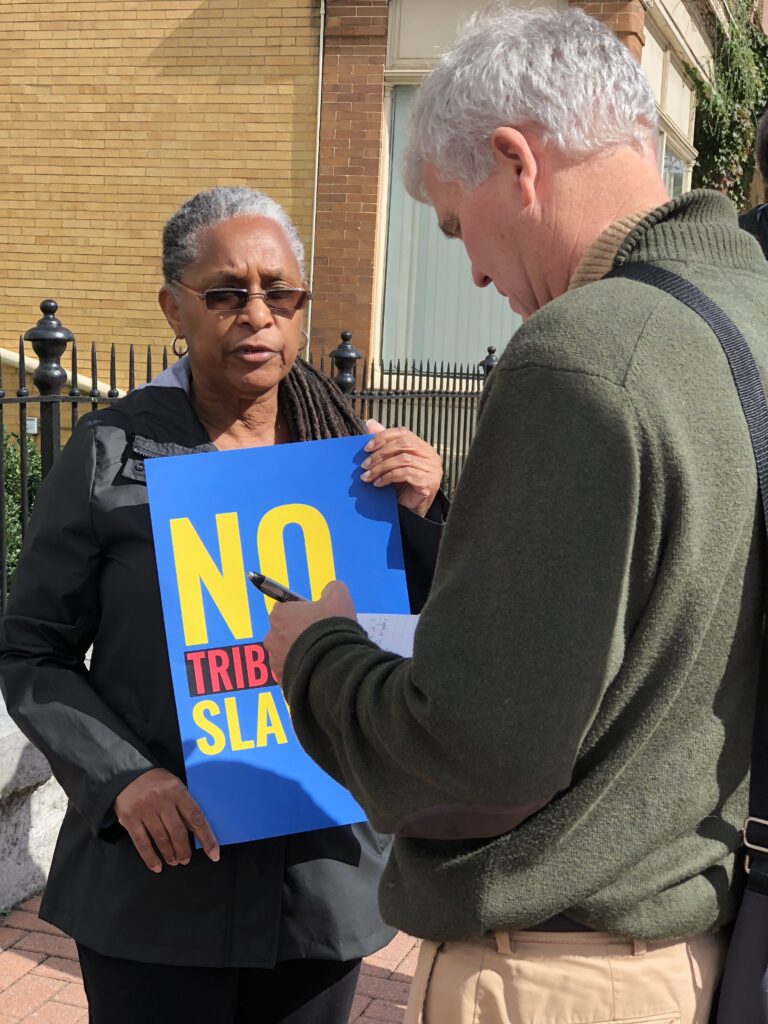

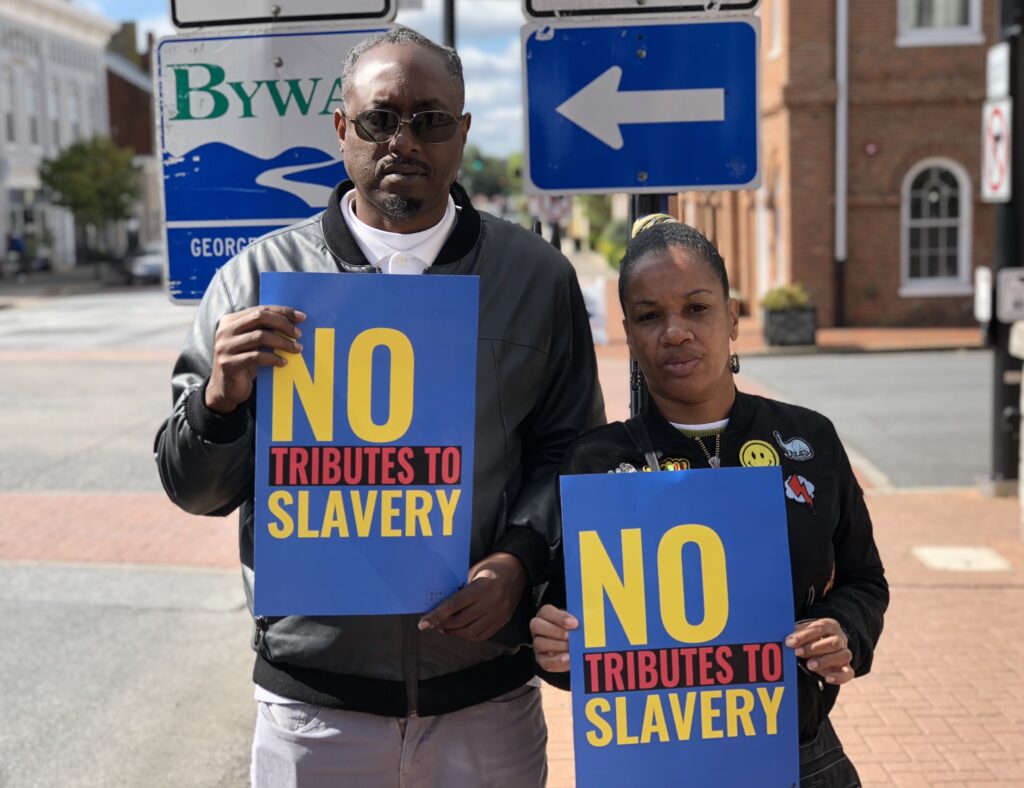

Beneath that are photos from the protest of the Confederate plaque on the Charles Town, West Virginia, courthouse on Friday, October 12. Among the protesters was the group of women whose joint letter launched the campaign for removal last year. Members of the West Virginia Women’s March were also involved in the demonstration, titled “Let’s Make It Right: Remove the Plaque.”

The following is adapted from “Heyward Shepherd ‘Tribute’ Is a Racist Relic That Must Come Down”:

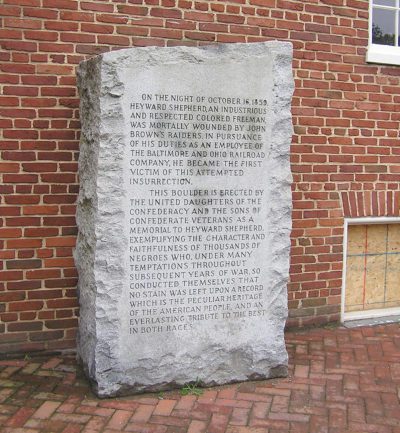

The inscription on what’s now known as the Heyward Shepherd memorial in Harpers Ferry makes clear that while it is a monument to many things—racism, slavery and oppression above all—Heyward Shepherd the human being is not among them.

Shepherd (whose actual first name was Haywood) had been a free black man, a baggage handler on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and a husband and father of five. As the first person killed in abolitionist John Brown’s failed 1859 attempt to incite an armed revolt among enslaved people, Shepherd’s accidental death was an historic casualty. The latter fact made Shepherd into a person of interest to the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). After learning that students at Storer College, an historically black institution in Harpers Ferry, had put up a plaque honoring Brown and his rebellion, the UDC endeavored to create an oppositional monument. Under the guise of honoring Shepherd, the Daughters savvily envisaged a way to exploit black death for their own propagandistic ends.

It ultimately took 10 years for the UDC to find a location that would permit installation of what they tellingly referred to as the “Faithful Slave Memorial.” Community opposition, which had been led by students and faculty at Storer College, was eventually overruled. In 1931—five years after erecting a monument to the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina, and five decades before installing an honorific to Confederates on the Jefferson county courthouse that replaced the building Confederates once destroyed—the UDC put up their monument along Harpers Ferry’s Potomac Street. Though it briefly acknowledged Shepherd as a “colored freeman,” it also contorted historical fact to disingenuously characterize Shepherd as having “exemplif[ied] the character and faithfulness of thousands of Negroes who, under many temptations throughout subsequent years of war, so conducted themselves that no stain was left upon a record which is the peculiar heritage of the American people, and an everlasting tribute to the best in both races.”

Like all Confederate markers, the Harpers Ferry monument perpetuates the ahistorical Lost Cause mythology that asserts the Confederacy’s treasonous fight to maintain black chattel slavery was valorous and that slavery itself was an ultimate good. But what’s particularly remarkable about the monument—an otherwise unremarkable 6’ tall slab of granite—is how it lays fully bare the intentions of those who put it there. The UDC’s outright support for racism is literally inscribed on its face. It is an explicit ode to slavery, a wistful longing for a time when black people knew their place, set into stone. The “best” blacks, it argues, did not fight for their freedom—not because they were outgunned and terrorized, victimized by a brutally violent and inhumane system—but because slavery actually wasn’t so bad. Consider that the UDC is credited with having erected the vast majority of the estimated 700 Confederate statues and monuments that dot this country. The story of the Harpers Ferry monument offers clarity on the ideas and beliefs that guided that work.

For good and obvious reasons—decency and morality among them—criticism of the monument continued after its placement. One scathing critique in the African-American press noted the marker proved whites in the South “still hanker[ed] for the filthy institution of slavery.” Those criticisms largely faded when the tablet was placed in storage in the 1970s due to construction, at least until the UDC demanded its return in the early 1980s, launching another round of justifiable outrage by groups including the NAACP. In response, the National Parks Service covered the monument with wooden planks, reportedly until the Sons of Confederate Veterans and UDC made direct appeals to Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond. The two Southern senators, whose legacies on race are both well-known and abysmal, saw to it that in 1995 the tablet was returned to the Harpers Ferry site where it still stands.

Even amidst a glutted field of racist markers, the Harpers Ferry monument stands out. The recent national conversation about the removal of Confederate iconography has pretty much omitted the Heyward Shepherd marker, but it should be a feature—as should the Charles Town Confederate plaque. In 1986, more than 120 years after the war’s end, the local UDC placed a marker to an enemy army that fought for slavery on the county courthouse, as if posting a literal sign about who could expect to receive justice inside. Defenders of Confederate markers frequently express fears that removing monuments that honor the Confederacy will magically “erase history.” They also argue that Confederate memorials weren’t intended to glorify slavery, and that calls to take these monuments down are the result of a new and misguided strain of “political correctness.” The Heyward Shepherd monument disproves both claims, despite what has been endlessly repeated by neo-Confederates from the streets of Charlottesville to the White House. Calls for removal around the country aren’t the result of some new PC movement. They’re the outcome when voices that have been ignored forever demand to be heard.

These monuments were put up to erase history and replace it with lies. To take them down, then, would be a corrective.