The 2018 U.S. midterm elections’ approach gives voters the chance to change the course of the country.

But lately, there has been a flurry of misinformation that may leave even the most confident voter feeling confused or discouraged about our election process.

To help connect voters to accurate information and restore faith in democracy, Steven Rosenfeld and Voting Booth have created A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election.

Below you’ll find everything you need to know, no matter what state you live in, about the 2018 midterm elections.

The guide (and handy resource links found throughout and at the end) in its entirety can be read below, or downloaded as a pdf to consult on the go.

To view or download the full guide for free, click here.

A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election

How to Make Sure You Are Eligible, and That Your Vote Is COUNTED

By Steven Rosenfeld

Introduction

The 2018 midterm elections are quickly approaching. These non-presidential elections historically give voters a chance to change the country’s course. They will decide whether or not Republicans keep a majority in Congress, important governor’s races and questions such as if voting rights will be restored to Florida’s 1.5 million felons.

This guide is intended to help new voters, infrequent voters and veteran voters have a better idea of what they must do to be able to vote and have their vote counted.

Unlike many democracies, the rules for voting in America vary state by state. In some states, it’s easier than others.

What’s often lost in the noise of toxic cable TV politics is the good news about our election system: The voting process has generally improved across America.

There are more ways to register to vote, more paper ballots in use, and more safeguards surrounding the process than ever, as 2018’s midterms approach. There are exceptions, of course—concentrated in a third of the country, mostly Southern and Midwestern states, where Republicans have made voting more arduous for presumed Democratic voters—notably among communities of color, poorer people, students, the elderly and people with disabilities. But as the fall of 2018 approaches, advocates of more inclusive and participatory democracy are winning, more than losing, lawsuits that challenge barriers.

On balance, there’s more progress than problems. However, the general observation, that if there’s a will in 2018 there’s usually a way to vote, is not what one readily hears. Not from some progressives, who say that voting is fraught and becoming more restrictive. Not from conservatives, who say illegal voting is rampant and want to over-police the process. Not from electronic voting machine critics, who say that it all can be hacked, so no result can be trusted. Nor from the front-page drumbeat about the ongoing threats from Russian intelligence meddling, carrying over from 2016’s election.

These narratives are based on shades of truth, some much thinner than others, and even falsities. They can be discouraging. They also share a common flaw, besides devaluing voting as a dignified individual act with societal consequences. That common flaw is that these storylines are too stark and ignore much of what voting is like in 2018.

How can this be? The answer is that the loudest voices focus on singular problems or villains. Activists attending the nationally renowned DefCon 27 tech convention say the threat is hacking. Congressional inquiries into Russian meddling say the top threat is sabotaging voters on Election Day. Lawyers filing lawsuits cite anti-democratic tactics like gerrymandering, or stricter ID laws and voter purges.

These are all real issues. They might affect you if you live in a less voter-friendly state. But they are not equally threatening across America. One rarely hears which threats are more prevalent in their state. Or what percentage of voters could be affected. Or what positive steps officials are taking. Without any of those contexts, it leaves a mistaken impression that voters and voting don’t matter much—when the opposite is true.

This short guide seeks to fill in these gaps as 2018’s midterms near. It’s not hard to register to vote. It’s not hard to overcome obstacles to getting required voter IDs. It’s not hard to get a ballot that will be counted. There is plenty of help if needed. It all starts with a desire to vote, and in rough scenarios, having perseverance and patience. The stakes in voting are high. Those seeking power, or seeking to stay in power, know it.

The voting process has requirements, but they are not mysteries. With three-quarters of states offering online registration, it has never been easier to get started. It’s no mystery which state election laws and policies affect voter turnout, for better or worse, and either side’s chances of winning. For Democrats to take back a U.S. House majority, we can be more specific than saying they need to win 23 more seats. Those voting for Democratic candidates have to overcome a 10-point popular vote advantage that the Republicans built this decade from gerrymanders and stricter voter ID laws. (We will discuss those issues after the basics.)

Most importantly, it’s no mystery what individuals must do to register, to vote, and cast a ballot that counts. That involves meeting registration deadlines, knowing where to vote, having the right ID if required, and giving oneself enough time to vote. It also is not hard to know what do if problems arise, such as not being on a polling place voter list or if a voting machine malfunctions. Besides taking a deep breath and being patient, there are established protocols to solve these snafus. Those steps are not complex.

It is also important to know what voters cannot control or do anything about on Election Day. Voters have to rely on preparations and precautions taken by local election officials across county, state and federal government. Fights over the choice of technology used, the way ballots are counted, or procedural transparency or the lack thereof, are for another day. Suffice it to say, however, that there are more cyber-security precautions underway for 2018’s midterms than has ever been the case—thanks to Russian meddling in 2016.

Voting in America starts with registration (except in North Dakota) and ends with certifying the count. In between are many steps, some never seen by the public. Voters don’t need to know all of the technicalities. They need to know their state registration deadlines, how they are going to vote (by mail or in person), when they are going to vote (before or on Election Day), their state’s voter ID requirements to get a regular ballot, and what to do if snafus arise.

So let’s go through these steps. These are the basics of voting. Then we can briefly turn to more political topics such as which voting rules help or hurt one side, what the Russians did and didn’t do in 2016 and how that affects the midterms, and why online platforms might be filled with misinformation to discourage voters—which should be ignored.

Guide—Part One: How to Vote

Chapter 1

Step One: Get Registered

Every state except North Dakota requires residents to register to vote. This can be done in three-quarters of the states by going online, or by paper applications mailed in or filed in person.

To vote in national and state elections in America, you have to be a citizen, age 18 or older, and register with your state before its deadline. In most states, that means going online to a state website and filling in basic information—or filling out and mailing in a paper registration form found at all post offices (or doing that in person at a county election office).

Increasingly, states are helping people to register. Thirty-seven states and Washington, D.C., offer online registration (here is a chart of those states). Motor vehicle agencies ask if you want to register when getting or renewing your license. As of mid-2018, 10 states are registering voters automatically when they get or renew a driver’s license, unless they opt out.

Seventeen states and Washington, D.C., also have same-day registration (see chart), meaning you can register and vote on the same day. In two of those states, Maryland and North Carolina, that option is only available during their early voting period (a window that ends before Election Day, which this fall is November 6, 2018).

While states have registration filing deadlines, it has never been easier to register. This chart has a state-by-state list of deadlines and same-day registration details.

What Information Is Needed?

You start by filling in your formal name (not nicknames!), residence address, mailing address (if it’s different from your home), date of birth, phone number or email (that’s optional—it’s used if there are any questions) and a government-issued ID number (usually your driver’s license or Social Security card number). Some states ask for your choice of political party. A few ask for race or ethnicity. Then you sign your name. (The U.S. Election Assistance Commission has this booklet with specifics for every state.)

Why do states want this information? An accurate home address ensures you get the correct ballot, as candidates and questions differ as you move from national to state to local races. The same goes for political party, whose primaries nominate candidates for the general election. State parties vary on whether anyone can vote in their primary if they have not already joined that party. (Independents have the best chance.) Race and ethnicity are for federal oversight—based on past state histories of discrimination.

Birthdays, driver’s licenses or Social Security numbers are used to verify identity. (The state will assign an ID number if you don’t have these government IDs.) These numbers are also used to keep voter lists current after people move, marry and change their names, or die. The signature is a legal oath that your information is true. It’s also printed in poll books at precincts, where you sign in to receive a regular ballot, and used in other ways—such as checking the ballot envelope if you’re voting by mail.

What Can Go Wrong?

Chances are you won’t misspell your name when registering online. But if you don’t register online and your handwriting is sloppy, a clerk in a county office could misread your name and put a typo in their computerized voter database. That snafu has led to people showing up at the polls and not finding their names in voter lists. That scenario is never pleasant—but can be resolved with patience (more on that shortly).

There’s another version of being sloppy when filling out a registration form (even online) that could come back to bite you: a messy signature. Make sure how you sign looks like what you normally do. Nobody wants a poll worker or party official to think that your signature does not match what’s on your registration form—which is in the poll book. That scenario also can be resolved, but it can be avoided by signing clearly.

Registering online is the best option. Once you’re in the system, you’re in it. The biggest complaint from officials about traditional voter registration drives is they dump a pile of paper applications to process at the last minute. In Georgia, the top state election official, Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican running for governor this fall, did not process tens of thousands of paper forms turned in by a Democrat-led drive in 2014. (Stacey Abrams, now running against Kemp, led that effort.) We will skip Kemp’s rationale. Had those people registered online, they’d have avoided his obstruction.

How does one register online? Type “Secretary of State” and your state’s name into an online search, and a registration portal will appear. Register directly with your state—not with a group that may direct you to another portal. State governments, and then mostly counties, oversee elections. Cut out the middlemen. (Once registered, campaigns and activists will find you.)

Deadlines and New Voters

There are a few more things to know. Most important is that registration deadlines vary by state. The longest are 30 days before the next election. For 2018’s midterms, that falls in early October. Try not to wait until the last minute, as it may be harder to get someone on the phone should any questions arise. (This EAC booklet has state deadlines.)

The next thing is residency requirements. To vote, you have to be a citizen, be at least 18 and qualify as a state resident. Usually, that means living at the same address for 10 to 30 days. Residency mostly concerns first-time voters, especially students. They must decide between registering at their parents’ address (and getting an absentee, or mail-in, ballot from that home county) or registering where they go to school.

Sometimes, states and party officials oppose student voting. Students might hear scare tactics; such as that they could lose financial aid if they registered away from their parents’ home. That’s almost always not true, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law noted, writing, “There is a lot of misinformation out there regarding what can happen to students.”

Nonetheless, students who want to vote have to think ahead and not be scared off. For example, Republican-led New Hampshire just passed a law (aimed at students) that new voters be permanent residents, obtain a state driver’s license with 60 days of an election and register their cars in the state. But it doesn’t take effect until 2019—not this fall.

Movers and Infrequent Voters

There’s another category of people who need to be mindful about their voter registration status—whether it’s current or they have to update their information. These are people who were registered voters, but moved (inside their county or state), or changed their names (usually by marriage), or vote infrequently (such as only in presidential years). If you moved to a new state, you have to re-register all over again.

Twenty states allow you to update your registration at a polling place, or they track voters who move and automatically update that information for them. If you’ve moved, married or are an infrequent voter, the smart thing is to call your local election office (typically at the county level) and ask if your registration is current. The U.S. Vote Foundation has an online searchable directory to contact these local offices and officials.

If you have voted infrequently but want to vote this fall, you should check your status. Federal law lets states remove (or purge) inactive people if they have not voted in four years—two complete federal election cycles. Some red-run states, like Ohio, that have sped up that four-year timetable have been sued but have won at the Supreme Court. Others like Indiana have tried to do likewise, but have been blocked in court. The easiest way to check your status is to call your local election office.

Not-So-Fine Print

Finally, there are people who have lost their voting rights. Imprisoned felons can only vote in two states—Maine and Vermont. Other states have a range of steps if those individuals want to vote. In some states like Oregon, they can vote as long as they’re not in jail. In other states, there’s a formal process to regain voting rights. In four states they are permanently blocked, although the state with the most felons, Florida, will this November vote on re-enfranchisement. In every election, a few ex-felons register without realizing they may be breaking the law. People found mentally incompetent by a court also lose their voting rights.

There’s one other potential hurdle in a few states. A few states require registrants provide proof of citizenship with their applications to vote in their state elections—as opposed to registering and voting in federal elections. (In all other states, you register for both at the same time.) Those states are Alabama, Arizona, Kansas and Georgia. They have slightly different versions of this policy. Georgia, for example, may request proof if its databases can’t verify one’s citizenship. (These states have some of the least voter-friendly laws.)

The twist of requiring additional proof beyond the eligibility requirements to register takes us to voter suppression. While voter registration is easier than it has ever been in most of the country, in some red-run states, the incumbents have embraced a menu of tactics to discourage their opposition’s base from voting. The most common tactic is requiring voters to present specific state-issued ID cards to get a ballot. (Other states simply have you sign in at the polls, as that’s a legal oath affirming your identity.)

We’ll get to how to clear the voter ID hurdle shortly. But let’s first turn to voting methods and options. There are more ways to cast a ballot than ever. This can be done on Election Day or earlier. It can be done in person in several settings, or by mail. Not every state offers the same choices, but most offer several ways to vote (see this state chart).

Chapter 2

Election Season

There’s really no such thing as Election Day. There’s a voting season that starts weeks before, where people vote by mail, in-person at county offices, or at polls on the first Tuesday in November.

Just as there are more ways to register than ever, there are more methods and options to vote. Election Day is no longer a single day, now that 37 states and Washington, D.C., offer early in-person voting (see this state chart). Every state has versions of voting by mail.

Early voting can be done in-person, usually at a county election office. If you know the hours, you can simply show up and vote. You’ll typically be given what’s known as an absentee ballot, which is what you’d receive at home if you requested voting by mail. You fill the ballot out, put it inside the envelope, seal and sign it, and turn it in. Some states do not have early voting sites, but still let voters turn in an absentee ballot.

Nationally, the average early voting period starts 22 days before Election Day, which is in mid-October for the midterms. People interested in early in-person voting should call local election officials for days and times (see this directory). The only caveat about early voting is if there is only one location in a county, it could be busy—with long lines—on the last weekend. For overseas and military voters, the early period can be up to 45 days out.

Voting also is no longer confined to polling places. Three states vote entirely by mail—Oregon, Washington and Colorado. States like California are moving in that direction. Nationally, there are two categories of voting by mail. In 27 states, any registered voter can request an absentee ballot (see this chart). However, in another 20 states, voters have to cite a reason when requesting a mail-in ballot. That can be illness, disability, travel, religious observance, being a poll worker, or incarceration (see this state list).

There are a few things to keep in mind if you’re voting by mail. Besides voting, the envelopes have to be correctly filled out and postmarked on time to count. The most common mistakes that disqualify these ballots are they’re mailed after Election Day, the voter forgets to sign the ballot envelope, or uses a different envelope, or their signature doesn’t match what’s on their voter registration form.

Sometimes people mail absentee ballots late, get antsy, and then go to a polling place and insist on voting. Usually, they are given a backup ballot, called a provisional ballot, which has to be verified before it counts. But those folks are not voting twice. In every election, ballots are counted by category (absentee, early, precinct, provisional, military and overseas) and officials catch and reject any duplicates.

Chapter 3

Clearing the ID Hurdle

In some Republican-run states, laws require voters to present specific forms of state-issued ID to get a ballot. While this hurdle has discouraged some people from voting in the past, it is not hard to get that ID.

So you’ve registered. You’ve figured out when and where you want to vote. You’ve given yourself enough time to do it. What else do you need to do?

In some states, you have to present the proper form of state-issued photo ID to get a regular ballot. Or if you are a first-time voter using a mail-in ballot, you may have to include additional documentation before your vote will be counted. For years, lawyers fighting for a more inclusive electorate have called this tactic a form of voter suppression. They have quoted many Republican officials saying that it will peel off several points of voter turnout among Democrats who tend to lack this ID—youths, new voters and poorer people. Congressional investigators have found that is correct: Stricter ID requirements can undercut voter turnout by 2 to 3 percent in the fall. But this gambit is not new. The legal fights over voter ID have been going on since 2006.

If you live in a red-run state, you should check to see what the voter ID requirements are (see this chart). In blue states like California, you don’t have to show any ID, because if you sign in to get a ballot and you’re lying, you have just signed a criminal confession. Still, in 13 mostly red-run states, there are stricter voter ID laws than there were in 2010.

See what voter ID is required in your state. If you cannot get time off from work to get that ID, or the paperwork costs associated with doing so are prohibitive, there are groups like VoteRiders that will help you get it done. Non-whites are affected much more than whites, and confusion surrounding voter ID rules have prompted people to skip voting. However, in 2018, this hurdle—and how to clear it—is well known.

Chapter 4

Polling Place Issues

Sometimes voting is a breeze. You show up, sign in and vote, and that’s it. Other times it’s slow, delayed, confusing and chaotic. Either way, patience and some knowledge of the process is key.

People who vote in polling places and local precincts have a different experience than people who vote by mail (or vote early at county offices). In general, the biggest concerns for voting by mail is having the ballot envelope properly filled out and postmarked.

Voting at polling places is another story. Across America’s 6,467 election jurisdictions and 168,000 voting precincts, the experiences can really vary. There can be heckling by partisans on the street outside—or not. There can be lines and delays to check-in—or not. There can be informed poll workers (citizens nominally paid to run the process) at sign-in tables, or inside as precinct judges—or not. There can be voting machines that work—or not. There can be sufficient backup ballots and knowledgeable officials—or not.

Whether you are in a more functional or less functional polling place, the voting process is the same. So let’s go through it, especially for new voters. It starts with knowing when Election Day is. (That sounds obvious, but partisan disruptors have been known to tell people that their party votes on Tuesday—when Election Day is—and other parties vote on Wednesday.) This leads to a related point. You don’t have to stop or talk to anybody on the way into a polling place or while waiting in line. Political campaigns are legally required to keep a certain distance from the entrance.

Poll Location and Check-In

But let’s back up. You registered. That means you might receive, by mail, a voter guide with a sample ballot, which often includes statements from candidates, and pro and con positions on the non-candidate issues. That mailing also has one’s polling place location. Some states may only mail a postcard with the poll location. Voters who do not get this information should call their local election office. There are many polling place locator apps online, but it’s best to check directly with your local election officials.

On Election Day, give yourself enough time. (If you are going to be pressed, think about voting early if your state allows that.) When you get to your polling place, you have to check in. This is where you show your ID, if that’s required, or sign your name in a poll book, or sometimes both, and get a regular ballot. Then, you go inside, find a booth to privately mark a paper ballot or use a touch-screen computer, and turn in that ballot (in the folder given to you). Poll workers put the paper ballots into a scanner. You get an “I voted” sticker and you’re done. Voters with disabilities use special consoles.

What can go wrong? Well, every step of this process—for reasons that can range from simple human error, to poor planning by election officials, to bungling poll workers, to machines that malfunction, to rare but still real partisan power plays. In all of these cases, patience and perseverance are the key to casting a vote that will be counted.

Let’s start with long lines. Why would there be long lines? Maybe it’s a certain time of day and people are just showing up all at once. Maybe there are too many questions on the ballot and too few machines or voting booths, causing a voting traffic jam. No matter what, you have to be patient. Anyone in line will be allowed to vote, even if it’s past the official closing time. Check the weather. If it’s cold or wet, take a jacket and an umbrella.

Sometimes, long lines result from election officials making mistaken voter turnout estimates, as that translates into how many voting machines/booths are deployed. There is some chance that scenario will happen this fall, because midterm years usually are the lowest-turnout November elections. That’s mostly been true even in 2018, where there has been greater turnout by Democrats and less turnout by Republicans.

The Backup: Provisional Ballots

Once you’re inside, you have to check in to get a ballot. What happens if you know you have properly registered, but your name and street address are not in the precinct poll book? First, take a deep breath, and know there’s a process to fix this.

The first thing to check is if you’re in the correct polling place and precinct. (Many polls have multiple precincts.) If you are in the right location, but not in the poll book, you can re-register in states offering Election Day registration (see this list) and then get a ballot. If you’re not in one of those states, you will be given what is called a provisional ballot. (In 27 states, partisan “poll watchers” also can challenge a voter’s credentials, triggering a provisional ballot. That’s very rare, but we’ll get to what to do if it happens in a second.)

What is a provisional ballot? They are ballots combined with a partial voter registration form. A 2002 federal law requires every state to offer backup provisional ballots. A voter fills in some different identifying information (address, birthday, etc.—states vary here), so officials can verify your registration before counting your ballot. The most common reasons for issuing a provisional ballot are: voters showing up at the wrong precinct and demanding to vote; people who don’t have the required state ID; people not listed on a precinct voter roll; and people claiming they never got an absentee ballot in the mail. Provisional ballots also have been used as backup if electronic voting machines fail.

People filing provisional ballots have to make sure they are turned in at the right desk—for their precinct. In half the states, turning in a provisional ballot at the wrong precincts means it won’t be counted. This scenario has been called the “right church, wrong pew” problem: You’re in the right polling place but can’t turn it in at any table. The solution is asking the poll workers—and checking that they’re properly signed and turned in.

Most states make an effort to verify and count all of their provisional ballots. But that is not always true—because some states, like Georgia, will not count them if officials have not verified all of the voter’s registration information in three days following Election Day. In other states, like Illinois, voters might have to show up at election offices with additional identifying documentation within a week of Election Day for the ballots to count. Lots of people never make that trip.

Still, provisional ballots are the backup system in all 50 states. So if something goes wrong, despite being proactive with registering and having the right ID with you, fill them out carefully and turn them in. Chances are they will be counted more than not.

If, for some reason, a voter is having a problem with harassment while waiting in line, the precinct check-in process, or getting answers about provisional ballots, there are Election Day hotlines to call lawyers volunteering for a nationwide Election Protection project run by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. That toll-free number is 1-866-OUR-VOTE (687-8683).

Election protection lawyers will tell you exactly what to do, and if necessary, are ready to go into court on your behalf. They will also alert the media about egregious problems, from harassment of voters to undue partisan challenges to any real breakdown in the process.

(In 2018, they are aware a federal court order that for the past 30 years has restricted the Republican National Committee from unduly challenging voters under a “ballot security” pretext—saying people signing in at polls must present additional credentials [usually more ID]—may be repealed. If that happens to you—call them. They will be on it.)

Voting Machine Issues

Once signed in, voters get a paper ballot in a folder and are directed to private booths to fill it out, or they go to electronic voting machines where they touch the screen to make their selections.

Voting machine technology is a controversial topic. But recently there’s more good news than bad with the voting machines used across America. Three-quarters of the country now votes on ink-marked paper ballots, and that figure is growing. Paper ballots are the best way to ensure there is a record of every vote cast. Scanners count these ballots, which can be further examined in recounts and audits. (The newest scanners even compile digital images of all the marked ovals race by race, which have helped to transparently resolve who has won very close contests.)

The bad news surrounds the oldest paperless voting systems, which still are used in 13 states—and entirely across five states (Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, New Jersey, Delaware). The biggest problems with paperless technology are that there is no backup in case the computer memory fails, and the vote counting software is susceptible to hacking, which has been shown to be a possibility in academic settings. (See this chart of voting technology by state and county.)

What does this mean for voters now? It’s counterintuitive, but the visible breakdowns on paperless machines are well known by now, as are their causes and fixes. For example, a decade ago, it was not uncommon for touch-screen users to select one candidate but see another candidate’s name appear. However frustrating it may be, the issues that have bothered activists and academics the most—hacking the results—are concerns voters cannot do anything about while they are using these machines on Election Day.

(There has been considerable speculation about how these machines have been remotely accessed to alter the reported counts, especially in elections immediately following wide deployment a dozen years ago. But nobody has come forth with incontrovertible proof—as opposed to dots pointing in suspicious directions—of hacked federal election votes.)

If you are voting on a touch-screen system and experience a problem, what do you do? You pause, ask poll workers for help, and either use another machine or insist on using a paper ballot backup. That sounds frustrating. Yet there is only so much a voter can do in that moment. You don’t have to be shy here. Voters make mistakes marking ballots all the time. Poll workers give them fresh ballots. They have a process for spoiled ballots. The pragmatic answer here is to speak up if something isn’t right with a machine.

With few exceptions in 2018, electronic voting machine breakdowns are not likely to be a major issue for most voters this fall. That conclusion even extends to the one threat that no voter can do anything about—the prospect of intentionally altered or hacked results. Why? Because since April, most states and the federal government have undertaken unprecedented cyber-security precautions surrounding the computers used in voting. Congress appropriated $380 million to secure these systems from Russian hacking. Ironically, it took a foreign power for election officials to take hacking seriously.

What About Russia?

Russia’s biggest impact in 2016’s election—and since—has been in the realm of political propaganda, not hacking elections. It’s much simpler for their intelligence services to get into the email accounts of relatively low-budget congressional campaigns, or put up fake personas on online platforms like Facebook, than to hack into government computers—especially now that the feds and states are watching. That distinction, however, has not been widely understood by many reporters writing about Russian threats to voting.

There are different computer systems used in voting. That’s intentional. Registration databases are one system. Counting the votes is another system. They are not the same. They are not connected. In 2016, Russian intelligence agency hackers targeted election systems in 18 states and voting-related websites in another six. (That’s apart from the ongoing hacking attempts on government computers by all kinds of interlopers.) The statewide voter registration database in Illinois was the only network breached, according to every federal investigation and report issued. No vote-counting system was successfully hacked, investigators in Congress and at intelligence agencies said.

What does all this mean for 2018’s voters? The biggest worry—which states and federal officials are watching out for—appears to be the possibility of intentionally scrambled voter rolls or scrambled poll books, because that data comes from the voter registration records. If that were to happen, voters would have to be patient, as election officials (or even courts) step in to ensure the election continues. That is the worst-case scenario.

But missing voters is a problem that election officials have faced before—for reasons that have nothing to do with Russia. In 2018’s primaries, voter rolls got mangled in Maryland and Los Angeles, California. In Maryland, the state motor vehicle agency didn’t forward new voter registrations to election officials, affecting about 80,000 people who ended up voting with provisional ballots. In Los Angeles, about 120,000 voters were also not put on voter lists. They also ended up using provisional ballots.

The Long View

The voting process has requirements, steps to be followed, potential bottlenecks and procedural hurdles, and backups if things go wrong. Those complexities raise larger questions, starting with, “Can voters trust this process?”

The answer is yes. We have to. We have no choice. Also, across America, most of the people running the nuts and bolts of elections are career civil servants dedicated to voting. They are not cut from the same cloth as politicians and political appointees who see elections as the pliable path to obtaining power. While there is some overlap, civil servants, as a profession and culture, believe in participatory democracy.

Despite the process’s pluses and minuses, voting is how citizens change or sustain our political system’s leaders. If the stakes in voting weren’t high, or if voting didn’t have an impact, you wouldn’t find all these political efforts in some states to make the process harder for the opposing party’s base.

As we look toward 2018’s midterms, the good news is that voting has become easier and more trustable in most of the country. That reality can be seen in more options to register, more ways to vote and wider use of paper ballots. In other parts of the U.S. where voting is more arduous, voters are not without help. When it comes to getting voter ID in states with stricter laws, non-profit groups are poised to help people. If there are Election Day instances of harassment or obstruction, civil rights lawyers can be easily and quickly reached. There are also fail-safe systems, especially provisional ballots, which, when properly filled out, will be validated and counted in most states using them.

Guide—Part Two: A Deeper Look at 2018’s Landscape

With the basics behind us, let’s take a closer look at what can go wrong. In some states, winning the statewide popular vote won’t mean winning local races. There will be lots of noise about rigging votes and stolen results.

This guide’s more optimistic view about voting in 2018 has some exceptions. There are a handful of states where it is harder to vote than in others—where voting is more difficult than it should be. Voters living there have to pay more attention this fall. But the partisan reasons behind those obstacles are not new to the 2018 midterm or those state’s political minorities.

This guide’s next part will discuss some of the biggest state-based factors that can affect voting and turnout in 2018’s midterms. But if you read no further, the takeaway is this: Get registered or update your voter registration information; have the required voter ID; know where and when to vote; and go forward with some knowledge about what to do if something goes wrong. But most of all, be determined to vote. Voting matters.

Domestic and Foreign Propaganda

Keep that focus. As Election Day approaches, there will be many alarmist reports about how the process is threatened. Some of these will be on social media—possibly planted there by adversarial foreign governments, and more likely posted by domestic activists and even professional provocateurs who traffic in political conspiracies. This trend isn’t exactly new, but it has flourished on social media in recent years.

Voters should be skeptical of all claims that the sky is falling on American democracy. Clearly, the electoral process could always be better, from any number of standpoints. The top question to keep in mind when you hear about threats is how many voters are being affected. What’s the possible impact, literally, percentage-wise, on an affected electorate or decision? That context is almost always missing in alarmist accounts.

That omission does not mean that small details in the process do not matter. To the contrary, they do, especially in low-turnout elections. That’s when the menu of slights that tilt the partisan playing field or discourage participation can have the most impact. This part of the guide will highlight some of those barriers. But in higher voter turnout years, those additional hurdles are usually overcome by the voting wave.

How High a Blue Wave?

Will 2018’s midterms become a wave election, surmounting the impediments that have stopped Democrats in red-run states from winning in more typical years this decade? There are plenty of signs it will be a wave year, but the open question is will it be a sufficiently large wave to wash away the anti-participatory features in your state.

Let’s start with the big picture. In Congress, Republicans hold a one-seat edge over Democrats (and two Independents who side with Democrats) in the Senate. Republicans also hold a 23-seat majority in the House of Representatives. At the state level, there are a handful of states where term limits have meant incumbent Republican governors have to leave office—such as Florida, Ohio, Nevada, Maine and New Mexico. There also are open governor’s seats in Georgia and Michigan. These are all important contests.

For Democrats to win back power, there are two different dynamics in play. For statewide races, such as governor and Senate, the statewide popular vote winner will be the victor. But that’s not what’s going on with House and state legislative seats in a third of the country. In those red-run states, election district boundaries were redrawn in 2011 by Republicans to segregate voters and to advantage their party. That is gerrymandering, where the political map is cracked and packed, so winning a statewide popular vote has nothing to do with winning a majority of U.S. House or state legislative seats.

As the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law explains, the “Democrats would have to win the national popular vote by 10.6 percentage points, or benefit from extraordinary shifts in partisan enthusiasm, in order to win a majority in the next House… There is a real risk that Democrats will win the national popular vote but will not win a majority of House seats—something that also happened in 2012.”

In these Republican gerrymandered states, Democrats would need to see closer to 60 percent of registered Democrats in that district turning out and voting, or, as the Brennan Center puts it, shifts in “partisan enthusiasm”—meaning Independents and Republicans voting for Democrats (or not voting)—for Democratic candidates to reach a majority.

Gerrymanders are how the GOP created a starting line lead—by segregating each party’s known voters after the last U.S. census. (The next census is in 2020.) Requiring stricter voter ID to get a ballot is more of a finish-line tactic, as that requirement peels off a few more points from likely blue voters. Together, gerrymanders and stricter ID laws have given Republicans a 10 percent advantage in many states whose political complexions would otherwise be purple—a combination of blue and red. (These states include: Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin.)

Handicapping Your District

The non-partisan Cook Political Report has tracked and rated the likelihood of who will win the congressional and governor’s races for many years. Their late August forecasts have 29 House races tagged as “toss-ups,” meaning anyone can win. Twenty-seven of these seats are now held by Republicans—largely the result of 2011’s gerrymander (see this chart). The report lists eight 2018 Senate races as “toss-ups,” with five of those seats held by Democrats (Florida, Indiana, Missouri, North Dakota and West Virginia), two open seats (Arizona and Tennessee), and a Republican incumbent in Nevada (see this chart).

Intriguingly, none of the endangered House seats are in the same states as endangered Senate seats. The reason for that is the House seats are mostly suburban districts where President Trump’s Republican Party is vulnerable, whereas the contested Senate races fall in predominantly rural states where the president’s party is more popular.

If you’re a voter in one of the contested or toss-up House districts, you can tell how tight the race is likely to be. Look at the latest polls for where you live and find what percent of voters are backing a “generic” Democrat and a “generic” Republican candidate. That figure tells you what’s happening after factoring in the impact of gerrymanders—as it’s based on all of the district’s voters.

But you’re not yet done. If you’re in a state with stricter voter ID, subtract 2-to-3 points from the percentage of voters supporting the generic Democrat. Are you still above 50 percent—a winning popular vote? The states with the most recently passed or modified stricter ID laws are Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota and Texas.

If you’re in a state, like North Carolina, where (besides gerrymanders and tougher ID) the legislature has cut early voting on the last weekend before Election Day (typically when Black clergy leads congregations to vote), you might have to subtract another point. The same goes for Ohio, where early voting was reduced and same-day registration was eliminated.

There are yet still other factors than can undermine vote totals—factors that are rarely mentioned. Some votes on electronic memory cards will get lost. Some paper ballots will get spoiled. Some scanners will misread paper ballot ovals. Some people submitting provisional ballots won’t present their IDs at county offices as required.

Stepping back, despite all the pollsters and pundits you will see and hear between now and Election Day, nobody really knows where the final swing voters, in the final swing neighborhoods, in the final swing counties will be.

That’s why Republicans, the authors of the most restrictive voting laws this century, push statewide measures like stricter voter ID, more limited registration, fewer early voting days, etc. They never know what will be determinative. They cast a wide net to hedge their bets. And that’s why Democrats will need turnout and popular vote margins above the 10.6 percent national average projected by the Brennan Center to win certain districts.

Half the States Have Races With National Impact

For the public, this political landscape shadowing the voting process underscores that voting does matter. What’s especially intriguing with 2018’s midterm elections is that unlike presidential years, when that race comes down to a handful of narrow margins in swing states—Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania in 2016—the contests that will decide who controls Congress starting next January are found in half of the states.

The vulnerable Republican congressmen and women are in California (districts 10, 25, 39, 45, 48), Colorado (6th), Iowa (1, 3), Illinois (6, 12), Kansas (2, 3), Kentucky (6th), Maine (2nd), Michigan (8, 11), Minnesota (2, 3), North Carolina (9th), New Jersey (3, 7), New York (19, 22), Texas (32nd), Virginia (7th) and Washington (8th). The Democratic toss-up races are open seats in Minnesota’s first and eighth House districts.

In the Senate, the vulnerable Democrats are in Florida, Indiana, Missouri, North Dakota and West Virginia. The vulnerable Republican incumbent is in Nevada, and there are open seats in Arizona and Tennessee.

The most nationally important governor’s races—because electing Democrats would mean veto power over red majority legislatures drawing gerrymandered maps in 2021 (after the 2020 census)—are in Wisconsin, Ohio, Florida, Georgia and Michigan.

All of these important races mean that voting in 2018’s midterms is significant. That process starts with registering before midterm deadlines fall. It continues with knowing where and when to vote. In some states that means having the required state-issued IDs. National advocates like VoteRiders can help people get those IDs. On Election Day, it means being patient and knowing that lawyers will have your back if needed (from the national hotline created by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law).

It all starts with a determination to participate. Don’t let anyone tell you that your vote or voting doesn’t matter. It’s the means individual citizens have for changing or keeping the country’s political direction.

Resources

There are many online resources that voters can use to find out about the specifics of voter registration, voter ID requirements, early voting and absentee voting, and help with the process.

Here’s a quick list of resources cited in this guide:

- Directory of local election offices and officials: https://www.usvotefoundation.org/vote/eoddomestic.htm

- Voter registration specifics (state by state): https://vote.gov/files/federal-voter-registration_1-25-16_english.pdf

- Voter registration deadlines (state by state): https://www.vote.org/voter-registration-deadlines/

- Online voter registration states: https://www.eac.gov/voters/register-and-vote-in-your-state/#tabs-2

- Election Day registration states: https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/vrm-states-portability

- Voter ID requirements (state by state): https://www.voteriders.org/get-voter-id/voter-id-info-cards/

- Financial assistance getting required voter IDs: https://www.voteriders.org/

- Provisional ballot rules (state by state): http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/provisional-ballots.aspx

- If you don’t have ID at polls and fill out a provisional ballot, post–Election Day deadlines to present ID at county election office: http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/voter-id.aspx#First

- Absentee ballot and voting by mail (state by state): https://www.vote.org/absentee-voting-rules/

- Chart of most gerrymandered states: https://www.azavea.com/blog/2017/07/19/gerrymandered-states-ranked-efficiency-gap-seat-advantage/

- Voting machine technology used (state and county): https://www.verifiedvoting.org/verifier/

- Election Day election protection legal network: http://866ourvote.org

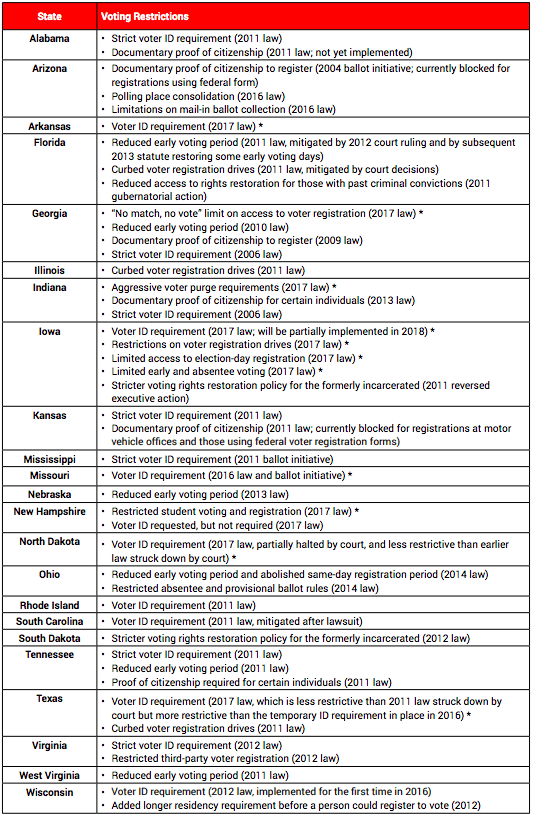

This chart of 2018 voting restrictions was prepared by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law and is from their report “The State of Voting 2018”:

The Brennan Center notes: “An asterisk (*) denotes a voting requirement that will be in place for the first time in a federal election this November.”

The Brennan Center notes: “An asterisk (*) denotes a voting requirement that will be in place for the first time in a federal election this November.”

Steven Rosenfeld is a senior writing fellow and the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He is a national political reporter focusing on democracy issues. He has reported for nationwide public radio networks, websites, and newspapers and produced talk radio and music podcasts. He has written five books, including profiles of campaigns, voter suppression, voting rights guides and a WWII survival story currently being made into a film. His most recent book is Democracy Betrayed: How Superdelegates, Redistricting, Party Insiders, and the Electoral College Rigged the 2016 Election (Hot Books, March 2018)

Copyright © 2018 by the Independent Media Institute

A Voter’s Guide to the 2018 Election by Steven Rosenfeld, produced by Voting Booth, a Project of the Independent Media Institute, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.