Performing elephants are denied all that is natural to them and are forced to endure beatings, electric shock, food and water deprivation and intimidation.

By Dee Gaug, Independent Media Institute

9 min read

No matter what political views or affiliations people in the United States might have, most of them would agree that animal abuse is just plain wrong. Animals who are kept in captivity or are forced to perform in circuses are subjected to some of the worst kinds of abuse. Among all these animals, however, elephants suffer the most in captivity as they are highly intelligent and social beings, according to experts, and have complex physical and social needs that cannot be met in any circus or zoo environment.

“Elephants who are kept in small enclosures are in increased danger of developing chronic foot disease and arthritis, both of which lead to frequent instances of death for captive elephants,” according to Dr. Toni Frohoff, a biologist and behavioral ethologist. “In fact, the most common reason for premature death of captive elephants is lack of space and standing on hard and/or otherwise inappropriate surfaces.”

Many people are unaware that circuses are still part of the American culture. The closing of the infamous Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in May 2017 did not mark the end of cruelty perpetrated on elephants, who are forced into captivity and made to perform in circuses. Between 25 and 30 traveling circuses, which include caged wild animals, continue to travel and operate in the United States. There are currently more than 60 elephants and hundreds of other animals still being used for human entertainment. Circus animal cruelty and exploitation are rampant. Some operators like Loomis Bros. Circus and Carson & Barnes Circus continued operating throughout the worst of the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and were once again advertising their show schedules for the spring and summer season in 2021. Currently, Carden Circus, Loomis Bros. Circus, Carson & Barnes Circus, Tarzan Zerbini Circus, and others are back on the road with elephants and other wild exotic animals.

Performing elephants are deprived of all that is natural to them. The methods used to train a wild animal into submission include beatings, electric shock (hot shots), food and water deprivation, and brutal intimidation. Elephants do not stand on their heads, sit on stools, stand on their hind legs, or give rides to humans on their backs because they want to; they do it because they are forced to with brutal training methods, as exemplified in undercover videos that can be found on YouTube.

While the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been tasked by Congress to enforce the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), which was signed into law in 1966 and is the primary federal law that regulates the treatment of animals in research, exhibition and transport, the AWA provides only minimum acceptable standards and historically has rarely been enforced. A prime example of this lack of enforcement is the story of Nosey the elephant. Nosey was captured in Zimbabwe when she was two years of age in 1984 and was brought to a Florida ranch with 62 other young elephants. About two years later, she ended up in the hands of former circus clown Hugo Liebel. Liebel used Nosey to perform in his circus and dragged her all over the country in a filthy, dilapidated trailer for more than 30 years.

Over the course of the next three decades, Liebel would rack up about 200 violations of the AWA for things like chaining Nosey so tightly by both her front and hind legs that she could hardly move, failure to provide adequate veterinary care, and failure to have sufficient barriers to protect the public. Yet year after year, the USDA rubber-stamped his annual renewal license. Though Liebel was fined several times, these fines were so minimal that they hardly made a difference and were seen as a small price to pay to keep the circus operational.

Finally, in November 2017, authorities in Lawrence County, Alabama, seized Nosey after Liebel’s truck had broken down. She was subsequently placed at the Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee where she has been receiving much-needed veterinary care for the plethora of ailments she is suffering from as a result of her life on the road and in the care of her owners. She remains in the sanctuary and is thriving there.

Nosey’s story is unfortunately not unique. In fact, it is the norm. Many, if not all, circuses that are currently on the road have extensive histories of federal animal welfare violations related to the handling of their elephants. The USDA inaction makes them complicit in the neglect and abuse of captive elephants. As a result, captive elephants continue to suffer every day that USDA inspectors refrain from doing their jobs, either because they do not care or due to internal pressure that prevents them from doing so. “It feels like your hands are tied behind your back,” says veterinarian Denise Sofranko, who spent 20 years as an inspector, and was quoted in an article on the website of the nonprofit Lady Freethinker. “You can’t do many things you’re supposed to when it comes to protecting animals. You’re seeing inspectors so frustrated they’re walking out the door.”

Animal advocates have long demanded a change to the USDA’s policy of rubber-stamping annual renewal licenses for chronic AWA violators. Up until November 2020, exhibitors seeking an annual renewal license would sign a self-certification form stating that they were complying with the AWA. Even if the USDA had actual knowledge of noncompliance—such as recent inspections that revealed violations of the AWA—the USDA would still renew the license.

The USDA’s Animal Care division is responsible for inspecting more than 12,000 facilities and exhibitors, including circuses and zoos, to ensure these license holders are operating in compliance with the AWA. Unfortunately, the USDA appears to be more concerned with not burdening license holders than with protecting animals and the public. So pervasive is this problem that on April 4, 2019, more than 140 congressional members from both sides of the aisle signed a 16-page letter to Sanford Bishop, chairman of the Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, FDA, and Related Agencies, expressing concern that the “USDA is treating these regulated industries as customers, giving deference to those who can’t comply with the AWA’s modest requirements while giving short shrift to the animals and the taxpaying public.”

In fact, a February 2019 article in the Washington Post said that “USDA inspectors documented 60 percent fewer violations at animal facilities in 2018 from the previous year.” The number of animal welfare citations issued by the USDA fell markedly under the Trump administration, from 4,944 citations in 2016 to 1,716 in 2018, according to another article in the Washington Post published in August 2019.

It is not a stretch to say that the USDA is complicit in perpetuating animal cruelty. In February 2017, the USDA, without warning, removed animal welfare records from its website, according to an article in the Washington Post, prompting large animal welfare organizations such as the Humane Society of the United States, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and the Animal Legal Defense Fund—along with other animal rights groups—to file separate federal lawsuits for violating a prior congressional directive and obliterating all transparency. The USDA purged from its website the searchable database of AWA inspection reports and enforcement records on thousands of licensed facilities and operators that use animals without providing any explanations, leaving the public in the dark—a public who, along with animal protection organizations, relies on this information to monitor and expose potential animal abuse at these facilities. Critics of this move stated that this was an attempt to keep the USDA’s complacency a secret from the taxpaying public, who pay for the salaries of the USDA employees and for other ancillary expenses related to the operation of the agency, and avoid accountability for enforcing the Animal Welfare Act.

This purge sent chronic AWA violators a clear message that there would be no accountability for providing not only substandard care but also outright abuse of their animals. No longer would chronic violators fear public scrutiny.

Fortunately, in December 2019, Congress enacted a provision in the fiscal year 2020 appropriations bill issuing a clear mandate to the USDA to fully reinstate its searchable database, giving the public access to all the agency’s records. The bill, signed into law in December 2019, required the agency to restore the purged records on its website within 60 days of the bill’s enactment, and continue posting such records moving forward. The records are being restored, albeit very slowly.

In response to pressure from animal protection organizations and the public, in March 2019, the USDA sought public comments on proposed updates to its current licensing procedures and received a staggering 110,000 comments. After decades, this pressure finally prompted the USDA to amend its licensing requirements to eliminate automatic renewals. A May 2020 USDA press release stated, “With this change, licensees have to demonstrate compliance with the AWA and show that the animals in their possession are adequately cared for in order to obtain a license.” Under the new rule, which went into effect in November 2020, licenses are valid for three years and applicants must demonstrate compliance before obtaining a license. This does not necessarily raise the bar set almost 55 years ago. This simply means that if a previous licensee, with a history of repeat noncompliances, wishes to obtain a new license, they would need to demonstrate that they are in compliance with the AWA regulations on the day(s) the USDA inspector is present and before a license is to be issued. It is noteworthy that the AWA’s antiquated standards are much less stringent than those of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the preeminent accreditation body in the United States. USDA inspectors will now conduct pre-licensing inspections since there will be no more renewal licenses. Under these new rules, “an applicant who fails the first inspection may request up to two reinspections to demonstrate compliance.”

Despite this development, the proverbial fox is still guarding the henhouse, and only time will tell if these new rules will have the desired effect of affording greater protection for captive elephants. Real change will come only with public awareness and legislation. What can be done? You can contact your senators and representatives and urge them to support the Traveling Exotic Animal and Public Safety Protection Act, TEAPSPA, which, if passed, will effectively end traveling acts nationwide that use exotic animals. In addition, you can make the choice to boycott circuses and zoos that use exotic animals. As journalist and former editor for Vanity Fair magazine Graydon Carter once remarked, “We admire elephants in part because they demonstrate what we consider the finest of human traits: Empathy, self-awareness, and social intelligence. But the way we treat them puts on display the very worst of human behavior.”

###

Dee Gaug is co-founder and vice president of Free All Captive Elephants (FACE). Prior to her involvement with FACE, Dee worked as a trial attorney for 15 years. She has done pro bono legal work in both Massachusetts and Florida including for the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Dee received her BA in psychology from the University of New Hampshire and her doctorate in law from Massachusetts School of Law. In 2018, she was a panelist at both the Free the Oregon Zoo Elephants Conference and the Performing Animal Welfare Society’s International Captive Wildlife Conference. She has gone undercover on numerous occasions to document the living conditions of captive elephants in both circuses and zoos.

Take action…

The Traveling Exotic Animal and Public Safety Protection Act (TEAPSPA, H.R. 2863), introduced into Congress by Representatives Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ) and David Schweikert (R-AZ), would amend the Animal Welfare Act to prohibit the use of exotic and wild animals in traveling performances. A companion bill, S. 2121, was introduced in the Senate by Senator Bob Menéndez (D-NJ) and cosponsored by Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT).

Urge your senators and representatives to support TEAPSPA to help end wild animal suffering in traveling acts across the United States.

Letter to the editor…

Replying to “Glyphosate’s Toxic Legacy Exposed: Why This Weedkiller Should Be Banned,” by EFL contributor Stephanie Seneff, CounterPunch, July 2, 2021:

“This is a demonstration of the control the Ag-chemical companies have over our government. I lived in Iowa for decades and these companies ran the state. Even though during the 1960s and 1970s it was demonstrated that a farmer’s income would not drop—just his yields, without the use of most chemicals—the ag-chem groups keep pushing their poison. Hence, Iowa has some of the nation’s worst water quality. We knew then that killing Iowa’s waterways was not necessary but the chemical companies are powerful. I would love to see an agency set up who would put the citizenry first, not the corporations, as the EPA currently does.” —Larry Schlatter, Gambier, Ohio

Cause for concern…

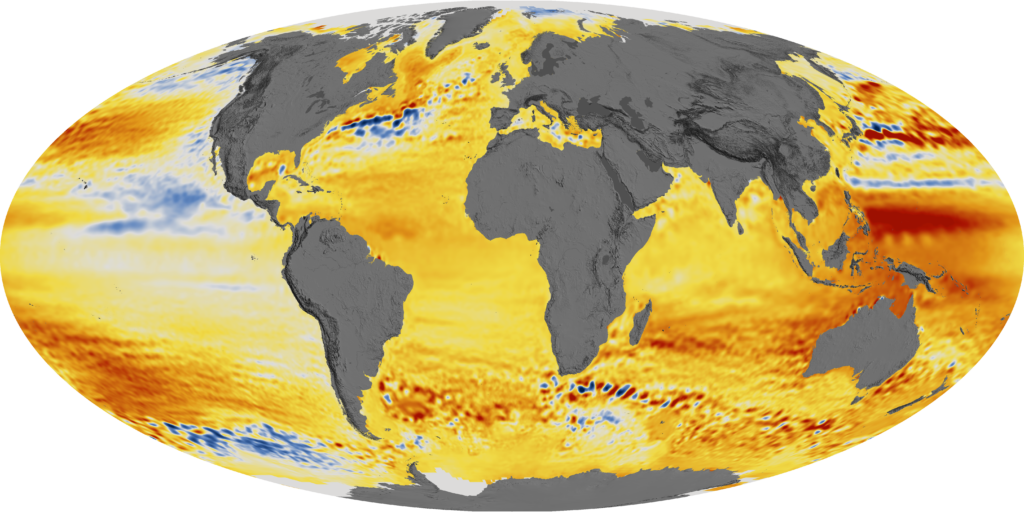

“We used to see our brothers and sisters in the Sahel leaving because of conflict and looking for better economic opportunities, but now it is climate change that is becoming one of the major drivers, pushing out people who can no longer cultivate their land,” said Landry Ninteretse, the Africa director for climate advocacy organization 350.org. “This is not only going to impact Africa, but also Europe, Asia, and America as well, as people seek safer places where they can live.”

- Madagascar’s famine is the first in modern history to be solely caused by global warming (Aryn Baker, TIME)

- Great Barrier Reef’s decline should be a wake-up call (Richard Leck, The Hill)

- America’s nuclear waste has nowhere to go and more is coming (Matthew Gault, VICE)

- Wildfire smoke may be even more toxic than previously thought (Yale Climate Connections)

- Is our reliance on air-conditioning warming the planet? (Richard Schiffman, Washington Post)

Round of applause…

“We have found, in our domestic and global advocacy and nutrition work, that for millions of people the suffering of animals in intensive confinement systems is a main driver of dietary shifts that are good for us, good for the planet and good for our fellow creatures,” writes Kitty Block, the president and CEO of the Humane Society of the United States and CEO of Humane Society International.

“When people see that pregnant pigs are confined in ‘gestation crates’ for months, unable to even turn around, trying to relieve stress by chewing on the bars of their crates until their mouths bleed, they can’t help but reexamine the true cost of their pork products. Both the marketplace and the public policy sector are already responding to consumer demand for healthier and more humane food choices. Giants in the food industry are diversifying their product lines and menus with plant-based offerings and a dozen states have passed laws that ban the intensive confinement systems responsible for so much animal misery.”

- Animal welfare must be central to reforming the food system (Kitty Block, Humane Society of the United States)

- Growing food justice by supporting Black farmers and a community-owned grocery store (Hannah Wallace and Tosha Phonix, Civil Eats)

- On this farm, cows don’t have to make milk and pigs sleep in (Melissa Eddy, New York Times)

- 49 delicious vegan BBQ recipes for summer parties (Kate, The Green Loot)

- These moths are so gorgeous they ‘put butterflies to shame’ (Shi En Kim, Smithsonian Magazine)

ICYMI…

“Just like our own ancestors, the precursors of today’s elephants originated in Africa. But while Homo sapiens evolved from their predecessors between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, modern elephants first arrived on the evolutionary map much earlier: 56 million years ago. Our arrival ultimately presented these majestic animals with their gravest threat, as we have killed them in great numbers for their ivory and destroyed their prehistoric habitats to make room for a host of human activities, from agriculture and logging to urbanization and other forms of land development. Now a new assessment of the pachyderms has revealed a stark reality and a turning point, something that conservationists have been worrying about for the past few decades: If poaching doesn’t subside soon and humans don’t stop encroaching on their ecosystems, wild elephants in Africa could become extinct in our lifetime.”

—Reynard Loki, “African Elephants Face Serious Risk of Extinction, Warns New Study,” Independent Media Institute, April 20, 2021

Parting thought…

“Animals should not require our permission to live on Earth. Animals were given the right to be here long before we arrived.” —Anthony Douglas Williams

Reynard Loki is a writing fellow at the Independent Media Institute, where he serves as the editor and chief correspondent for Earth | Food | Life. He previously served as the environment, food and animal rights editor at AlterNet and as a reporter for Justmeans/3BL Media covering sustainability and corporate social responsibility. He was named one of FilterBuy’s Top 50 Health & Environmental Journalists to Follow in 2016. His work has been published by Yes! Magazine, Salon, Truthout, BillMoyers.com, Counterpunch, EcoWatch and Truthdig, among others.

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.