When it comes to Monsanto’s controversial herbicide, both the mainstream scientific community and our regulatory establishments have failed us.

By Stephanie Seneff, Independent Media Institute

11 min read

The following excerpt is from Toxic Legacy: How the Weedkiller Glyphosate Is Destroying Our Health and the Environment by Stephanie Seneff, PhD (Chelsea Green Publishing, July 2021). It is reprinted with permission from the publisher and has been adapted for the web.

In September 2012, I attended a nutrition conference where Dr. Don Huber from Purdue University was speaking on the topic of “glyphosate.” Glyphosate is the active ingredient in the herbicide Roundup. While glyphosate isn’t a household name, everyone has heard of Roundup. Drive across the United States and you’ll see vast fields marked with crop labels that say “Roundup Ready.” Monsanto, the Missouri-based company that was Roundup’s original manufacturer, was acquired by the Germany-based company Bayer in 2018 as part of its crop science division. Monsanto has touted glyphosate as remarkably safe because its main mechanism of toxicity affects a metabolic pathway in plant cells that human cells don’t possess. This is what—presumably—makes glyphosate so effective in killing plants, while—in theory, at least—leaving humans and other animals unscathed.

But as Dr. Huber pointed out to a rapt audience that day, human cells might not possess the shikimate pathway but almost all of our gut microbes do. They use the shikimate pathway, a central biological pathway in their metabolism, to synthesize tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine, three of the twenty coding amino acids that make up the proteins of our body. Precisely because human cells do not possess the shikimate pathway, we rely on our gut microbiota, along with diet, to provide these essential amino acids for us.

Perhaps even more significantly, gut microbes play an essential role in many aspects of human health. When glyphosate harms these microbes, they not only lose their ability to make these essential amino acids for the host, but they also become impaired in their ability to help us in all the other ways they normally support our health. Beneficial microbes are more sensitive to glyphosate, and this causes pathogens to thrive. We know, for example, that gut dysbiosis is associated with depression and other mental disorders. Alterations in the distribution of microbes can cause immune dysregulation and autoimmune disease. Parkinson’s disease is strongly linked to a proinflammatory gut microbiome. As has become clear from the remarkable research conducted on the human microbiome in the past decade or so, happy gut bacteria are essential to our health, including in ways that researchers have yet to fully understand. It’s worth remembering that Roundup hit the market—and was declared safe—before much of this groundbreaking research on the human microbiome was ever conducted.

Dr. Huber also explained that glyphosate is a chelator, a small molecule that binds tightly to metal ions. In plant physiology, glyphosate’s chelation disrupts a plant’s uptake of essential minerals from the soil, including zinc, copper, manganese, magnesium, cobalt, and iron. Studies have shown that plants exposed to glyphosate take up much smaller amounts of these critical minerals into their tissues. When we eat foods derived from these nutrient-deficient plants, we become nutrient deficient, as well.

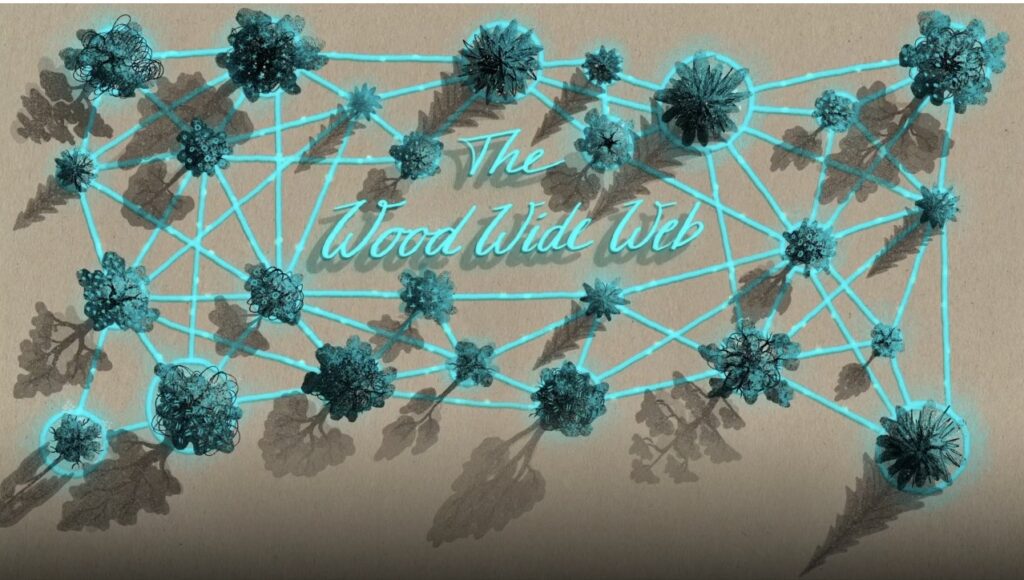

Glyphosate also interferes with the symbiotic relationship between plant roots and soil bacteria. Surrounding the roots of a plant is a soil zone called the rhizosphere that is teeming with bacteria, fungi, and other organisms. Glyphosate kills the organisms living in the rhizosphere, which then interferes with a plant’s nitrogen uptake, as well as the uptake of many different minerals. This interference further translates into mineral deficiencies in our foods. Glyphosate also causes exposed plants to be more vulnerable to fungal diseases. And fungal diseases can lead to contamination of our foods with mycotoxins produced by pathogenic fungi.

I came away from Dr. Huber’s lecture convinced that I needed to learn a lot more about glyphosate.

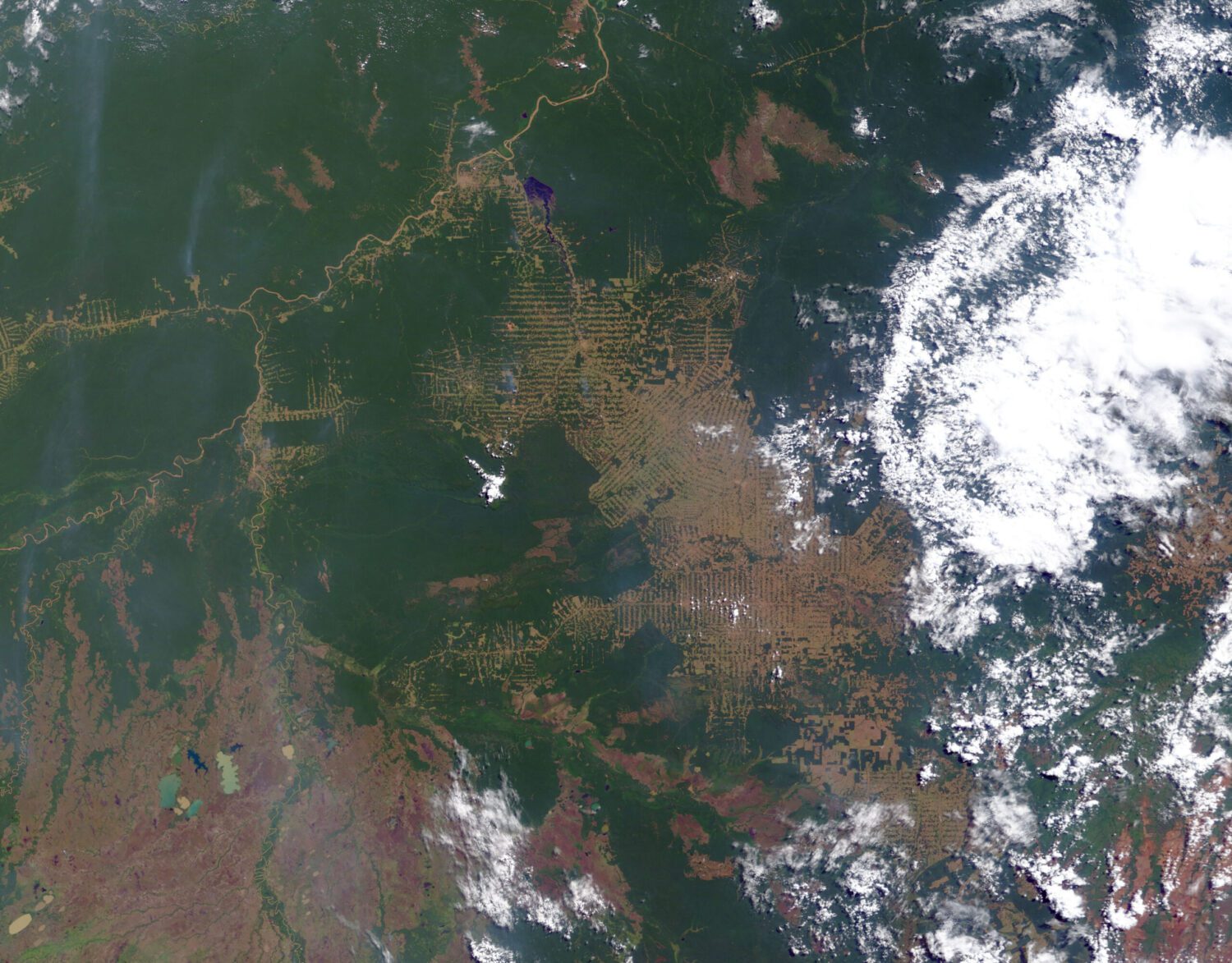

Fable for tomorrow

Both of my parents grew up on family farms in small towns in southern Missouri. The area is now an environmental and economic wasteland, because large agrochemical farming has forced most small farmers into bankruptcy. As a child, I visited my grandparents on their farms, gathering eggs from the chicken coop, marveling over the cows and their calves in the fields, and helping with the fruit stand where my dad’s parents sold apples and peaches. When I was 13, my grandfather was discovered dead on his tractor, with a split-open bag of DDT by his side.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Americans were told that herbicides and insecticides, such as DDT, were safe. DDT is an organochloride first used by the military during World War II to control body lice, bubonic plague, malaria, and typhus. While DDT was effective at preventing malaria, the environmental consequences of its use were devastating, especially as people began using it more and more, in broader and broader applications, for pest control.

I read Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962, shortly after it was published. A marine biologist by training, Carson condemned the chemical industry for its irresponsible disinformation campaign. She painted a grim picture of no birds singing in the spring. She called it a “fable for tomorrow,” a phrase that haunts me to this day. Silent Spring explores in detail how DDT and other chemicals were poisoning wildlife—from earthworms in the soil to juvenile salmon in the rivers and oceans. Carson’s book had a profound effect on me and helped me understand my grandfather’s untimely and unexpected death.

Around the same time, I also learned about the thalidomide disaster. Thalidomide, manufactured by a German pharmaceutical company, was prescribed to pregnant women to help with morning sickness and difficulty sleeping. It was aggressively marketed and advertised as safe. But thousands of children whose mothers took thalidomide during pregnancy were born with birth defects, including missing arms and legs. Studying the photographs of these deformed and unhappy children in a magazine, I realized that sometimes the products that purport to improve our lives can have major adverse effects—and that the companies that sell them cannot necessarily be trusted to tell us the whole truth about the risks their products pose.

The United States avoided this disaster, which devastated the lives of at least 10,000 children in Europe, because of a brave scientist named Frances Oldham Kelsey. Dr. Kelsey was a Canadian-born reviewer for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, responsible for approving or rejecting the application for a license to distribute the drug in the United States. Although she faced enormous pressure, and although thalidomide was already approved for use in Canada, Great Britain, and Germany, Dr. Kelsey rejected the application after she determined that there was insufficient evidence that it was safe to use during pregnancy. At the time, I was young, optimistic, and patriotic. I remember thinking how lucky I was to live in the United States, a country that protected its citizens from such a catastrophe.

Hiding in plain sight

In the 1950s, in the small town in coastal Connecticut where I grew up, living treasures were everywhere: ladybugs, dragonflies, butterflies, bumblebees, grasshoppers, lightning bugs, giant beetles we called pinching bugs, toads, and dozens of chittering playful squirrels. Praying mantises were a rare delight, but fireflies could be counted on in the evening, along with bats overhead as the shadows grew. Today I live outside Boston, in a place that has a similar climate to the Connecticut town where I spent my childhood. Yet it’s rare to see wildlife on our suburban street. An occasional squirrel, and one or two butterflies in the spring. No longer do we have to clean the windshield of all the dead bugs that accumulate on a summer’s day. Children, of course, don’t realize what they’re missing out on. This change appears to have happened slowly enough that almost nobody has noticed.

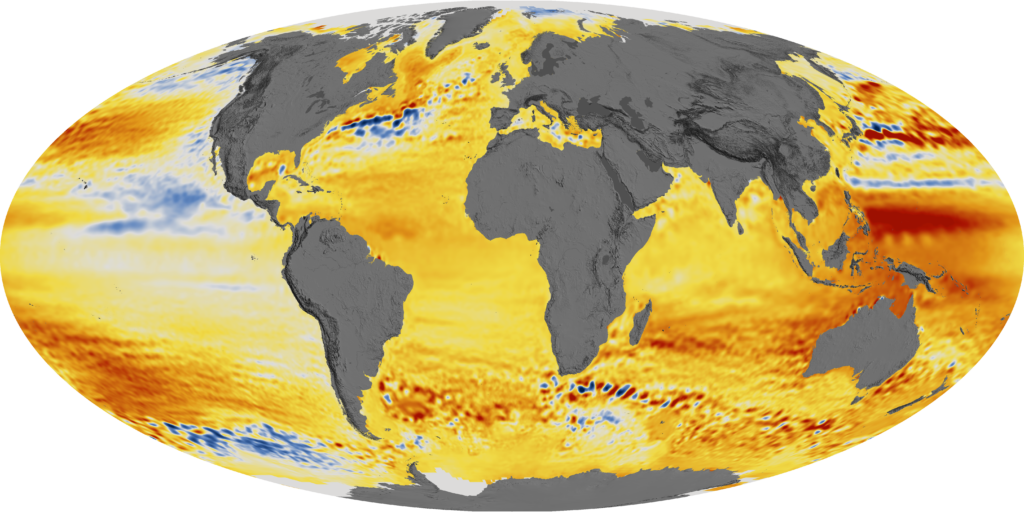

Yet, there’s no question that something devastating is going on, even if it’s difficult to name it precisely. The rate of species going extinct today is hundreds or even thousands of times faster than it has been during the past tens of millions of years. Environmental scientists warn that we have already entered the sixth mass extinction. Human health is also suffering. Over the past few decades an alarming rise in many chronic diseases across the globe has occurred, especially in countries that adopt a Western-style diet based on industrialized agriculture. Many of these diseases have an autoimmune component. They include Alzheimer’s disease, autism, celiac disease, diabetes, encephalitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and obesity.

Something terrible seems to be affecting every living thing on the planet—the insects, the animals, and the health of human beings, including children. Something hiding in plain sight. While we can’t reduce all environmental and health problems to one insidious thing, I believe there is a common denominator. That common denominator is glyphosate.

This problem is too important to ignore. My goal is to convince anyone who eats, anyone who has children, and anyone who cares about the health of humans and the planet that we need to look much more closely and much more carefully at the impact of glyphosate on and beyond the food supply. Both the scientific community and our regulatory establishments have failed us. It is time to shine light onto the shadows—to convince the world about glyphosate’s diabolical mechanism of toxicity and give ourselves the tools we need to understand how glyphosate harms us and what we can do to protect ourselves and our families.

Stephanie Seneff, Ph.D., is a senior research scientist at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. She has a bachelor’s degree in biology with a minor in food and nutrition, and a master’s degree, an engineer’s degree, and a Ph.D. in electrical engineering and computer science, all from MIT. She has authored over three dozen peer-reviewed journal papers on topics relating human disease to nutritional deficiencies and toxic exposures. She has focused specifically on the herbicide glyphosate and the mineral sulfur. Dr. Seneff is the author of Toxic Legacy (Chelsea Green Publishing, July 2021) and she lives in Hawaii.

Take action…

Several environmental, public health and consumer advocacy groups, including Friends of the Earth Action, Food & Water Action, Progress America and Corporate Accountability have sponsored a public petition urging the Environmental Protection Agency to ban the use of glyphosate.

Urge the Environmental Protection Agency to ban the use of glyphosate.

Cause for concern…

“The deadly collapse of a 12-story condominium tower on a barrier island north of Miami Beach early Thursday morning has spurred new calls to survey buildings in areas vulnerable to sea level rise and subsidence, highlighting one of the lesser-known threats of climate change,” report Alexander C. Kaufman and Chris D’Angelo for HuffPost.

- Miami tower collapse stokes new fears of rising seas (Alexander C. Kaufman and Chris D’Angelo, HuffPost)

- Unprecedented heat wave in Pacific Northwest driven by climate change (Anne C. Mulkern, E&E News via Scientific American)

- Bipartisan infrastructure deal omits big climate measures (Coral Davenport and Lisa Friedman, New York Times)

- Dispossessed, again: Climate change hits Native Americans especially hard (Christopher Flavelle and Kalen Goodluck, New York Times)

- EPA watchdog says Trump appointees kept fired employees on payroll (Alex Guillén, Politico)

Round of applause…

“Congressional Democrats have approved a measure reinstating rules aimed at limiting climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions from oil and gas drilling, a rare effort by Democrats to use the legislative branch to overturn a regulatory rollback under President Donald Trump,” reports Matthew Daly for the Associated Press.

- Congress votes to reinstate methane rules loosened by Trump (Matthew Daly, Associated Press)

- Shawnee reclaim the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio (Mary Annette Pember, Indian Country Today)

- Mapping quest edges past 20% of global ocean floor (Jonathan Amos, BBC News)

- 3,000 hospitals and schools add vegan burgers to menus (Nicole Axworthy, VegNews)

- How to reduce energy use during heat waves and peak demand days (Harvard University)

ICYMI…

“The southwestern states, in particular, have faced frequent and ongoing droughts over the past two decades, and traditional water supplies are failing,” writes Earth | Food | Life reporter Frederick Clayton, who explores how turning wastewater into drinking water can make existing water supplies go further (“The Southwest Offers Blueprints for the Future of Wastewater Reuse,” Truthout, April 17). “How a city can recycle wastewater depends largely on the geography of the area, financial resources—and, perhaps most importantly, the attitudes of the public.”

Parting thought…

“In terms of personal choices, let’s all think more carefully about where we get our protein from.” —Sylvia Earle

Reynard Loki is a writing fellow at the Independent Media Institute, where he serves as the editor and chief correspondent for Earth | Food | Life. He previously served as the environment, food and animal rights editor at AlterNet and as a reporter for Justmeans/3BL Media covering sustainability and corporate social responsibility. He was named one of FilterBuy’s Top 50 Health & Environmental Journalists to Follow in 2016. His work has been published by Yes! Magazine, Salon, Truthout, BillMoyers.com, Counterpunch, EcoWatch and Truthdig, among others.

Earth | Food | Life (EFL) explores the critical and often interconnected issues facing the climate/environment, food/agriculture and nature/animal rights, and champions action; specifically, how responsible citizens, voters and consumers can help put society on an ethical path of sustainability that respects the rights of all species who call this planet home. EFL emphasizes the idea that everything is connected, so every decision matters.

Click here to support the work of EFL and the Independent Media Institute.

Questions, comments, suggestions, submissions? Contact EFL editor Reynard Loki at [email protected]. Follow EFL on Twitter @EarthFoodLife.