For-profit operators and their investors use complex business arrangements and networks of related companies to enrich themselves and do little to improve education.

Ever since charter schools were created in the 1990s, there’s been a persistent question1 of whether or not the schools introduce an element of profit-making into the public education sector. In statutory law, legislatures have generally ruled that charter schools must be operated as nonprofits. In fact, only one state,2 Arizona, technically allows for-profit organizations to be licensed to run charter schools. Yet, the charter school industry has proven to be an innovator in developing business arrangements in which third-party and related organizations profit handsomely off a nonprofit charter.

One such entryway for profit-making enterprises to exploit charter schools, according to an in-depth examination conducted by Our Schools in 2021, occurs when for-profit charter school operators partner with private investors intent on turning quick profits from public dollars meant for educating children.

Our Schools examined the relationship between Pansophic Learning, owner of the Accel Schools chain of for-profit charter schools, and Safanad Limited, a private equity firm, originating in the Middle East, with extensive investment holdings in K–12 education, senior living, and other public sector-related enterprises.

What Our Schools found was that for-profit businesses like Pansophic Learning are providing entryways for wealthy investors from abroad to flood the U.S. with money to buy up struggling taxpayer-funded enterprises and put into place elaborate business schemes and networks of interrelated companies that hide their profiteering while doing little to improve the quality of services to the public.

A request for comment regarding Pansophic’s relationship with Safanad and the partnership’s potential for conflicts of interest that was left as a press inquiry at the Pansophic website did not receive a reply.

The combination of for-profit operators backed by private equity has become prevalent in other publicly funded sectors that have traditionally been operated by federal and/or state governments or nonprofit organizations. And the results have not been beneficial to the public or the individuals the publicly funded system was intended to serve.

For example, in the government-funded prison system, “The involvement of private equity firms, which manage large investment portfolios, presents a conflict between the financial and social goals of some investors,” reported Prison Legal News in 2019, citing two studies—one from the nonprofit Worth Rises, which advocates for “dismantling the prison industry,” and the other from the American Federation of Teachers, a national teachers’ union.

Another analysis, by the ACLU, found that for-profit prison operators backed by private investors are more apt to create profit for their investors by maintaining high rates of incarceration, which results in significantly higher social and fiscal costs to the public.

Our Schools found that this combination of for-profit entrepreneurs backed by private investors is having a similarly corrosive impact in the charter school industry.

Ron Packard and K12 Inc.

The genesis of Accel Schools goes back to 2014, when Education Week reported that Ron Packard, the former CEO of K12 Inc., had formed a new education enterprise called Pansophic Learning. K12 Inc., which changed its name to Stride Inc. in 2020, was then, and as of this writing still is, the largest for-profit charter school operator in the U.S.

Packard, a former Goldman Sachs executive who specialized in mergers and acquisitions, departed K12 Inc., which he founded, at a time when the company was besieged with negative publicity.

In 2011, K12 Inc. was the subject of a scathing story in the New York Times revealing that “only a third” of the students enrolled in its online charter schools “achieved adequate yearly progress, the measurement mandated by federal No Child Left Behind legislation,” while the company employed multiple ways to “squeeze profits from public school dollars by raising enrollment, increasing teacher workload, and lowering standards.”

The withering critique, which ran on the newspaper’s front page, “caused” the publicly traded company’s stock price “to drop precipitously,” Education Week reported in 2012, and prompted a shareholder to file a federal lawsuit accusing K12 Inc. executives, including Packard, of “misleading investors with false student-performance claims.”

More negative publicity came in 2013 when Politico reported K12 Inc. was one among many online charter schools that “posts dismal scores on math, writing, and science tests and mediocre scores on reading.” Another blow came that year when influential hedge fund manager and charter school proponent Whitney Tilson announced he was shorting K12 Inc. stock, betting the company would fail.

In 2014, K12 Inc. became the target of yet another lawsuit accusing the company of “misleading investors by putting forward overly positive public statements… only later to reveal that it had missed key operational and financial targets,” Education Week reported. The lawsuit also charged Packard, whose relationship to the company had become unclear, of selling off his own stock before revealing the negative financials, and, thus, earning a windfall of $6.4 million before the stock price plunged.

But as Packard disengaged from one troubled education enterprise, he started another with a financial partner that would provide the capital to quickly scale up.

As Education Week reported in 2014, Packard’s new company, Pansophic Learning, included a partnership with a holding company, Safanad Education, a subsidiary of Safanad Limited, a New York- and Dubai-based real estate and investment firm. Packard and Safanad spent an unknown sum to purchase part of K12 Inc.’s assets, mostly in higher education, and acquire an international brick-and-mortar private school. The two entrepreneurs were “on the hunt for acquisitions,” according to Education Week.

A Charter School Shopping Spree

Initially, Packard and Pansophic Learning kept a low profile until, in 2016, a visit by then-Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump drew attention to a Cleveland, Ohio, brick-and-mortar charter school “that usually escapes notice,” reported the Plain Dealer, a Cleveland newspaper.

According to the Plain Dealer, the school, the Cleveland Arts and Social Sciences Academy, was one of 27 schools in Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio that had been recently acquired by Accel Schools, a new for-profit network of charter schools owned and operated by Pansophic Learning.

Packard is listed as the CEO of both Pansophic Learning and Accel Schools. Two other C-suite executives of both Pansophic Learning and Accel Schools are COO Maria Szalay and CTO Eric Waller. Pansophic Learning and Accel Schools also have street addresses within 5 minutes’ walking distance of each other in McLean, Virginia.

Prior to the news about Trump visiting its school, Accel Schools had been “amassing an education empire” in Ohio, the Akron Beacon Journal reported.

Among its acquisitions were, in 2014, the “troubled K-8 schools” of White Hat Management, which had previously been, according to the Akron Beacon Journal, Ohio’s largest charter school chain. In 2018, Accel Schools purchased White Hat’s last remaining online charter school as well.

In 2015, Accel Schools also acquired the assets of another financially struggling charter management firm, Mosaica Education, and bought Cleveland-based I Can Schools, which, Packard told the Plain Dealer, were also “struggling financially.”

The charter school shopping spree Accel Schools went on undoubtedly benefited from the financial support of Safanad.

“We are fortunate to partner with Safanad,” Packard is quoted saying in Safanad’s official announcement of its partnership with Pansophic Learning in 2014. “Safanad’s extensive resources will allow us to pursue opportunities of all sizes,” he said.

The Bahamdan Connection

According to the firm’s website, Safanad’s founder and CEO is Kamal Bahamdan, a Saudi national. Kamal Bahamdan “was the CEO of the Bahamdan [investment Group],” according to his profile.

Kamal Bahamdan’s current relationship with the Bahamdan Investment Group is unclear, but the Bahamdan firm maintains a controlling interest in Safanad. According to its SEC filings brochure, Safanad is “controlled by Bahamdan Investment Group and KB Group Holdings Ltd.” KB Group Holdings Ltd., according to Safanad’s SEC filing form, is owned by the Bahamdan Investment Group.

The Bahamdan Investment Group is a Saudi-based investment firm founded by Salem Bahamdan, Kamal Bahamdan’s father, according to ZoomInfo. Kamal Bahamdan is the grandson of Abdullah Bahamdan, according to Wikipedia.

In numerous online profiles, Abdullah Salem Bahamdan (also Abdullah S. Bahamdan, Abdullah Salim Bahamdan, and Abdullah Bahamdan) is described as a “seasoned banker” and one of “the Middle East’s most prominent and influential financiers.”

Abdullah Bahamdan also spent more than 50 years as the chairman of “Saudi Arabia’s National Commercial Bank, the largest lender in the Arab world,” according to Institutional Investor. National Commercial Bank (NCB), which merged with Samba Financial Group in 2021 to form Saudi National Bank (SNB), was established in 1953 by royal decree, according to the SNB website, with the Saudi government as its major shareholder.

Despite its close relationship to the Saudi government, NCB was one among 16 financial institutions that were fined by the Saudi Monetary Authority in 2019 “for violating principles of responsible finance,” according to Reuters. “[T]he violations were related to exceeding debt burdens imposed on people in proportion to their monthly income.”

In 2020, the U.S. Treasury Department settled a lawsuit with NCB accusing the bank of violating U.S. sanctions against Syria and Sudan between November 2011 to August 2014.

The bank and Abdullah Bahamdan have been the subjects of at least two lawsuits accusing them of financing terrorist groups, which may have been part of what prompted the Saudi government to, in 2017, “crack down on corruption” in its banking industry, Reuters reported.

Perhaps as a result of the crackdown, SNB, as of 2019, claimed on its website that it “developed a Bank-wide Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorist Financing Policy.”

Mixing Charter School Investments With Subpar Senior Care

Aside from its investments in Pansophic Learning, Safanad has made some of its biggest commercial real estate deals in the health care sector, principally in senior care facilities, including assisted living, independent living, memory care, and nursing homes, frequently called skilled nursing facilities.

Senior Housing News reported that Safanad teamed up with investment firm Formation Capital, an Atlanta-based health-care-focused private investment company, to purchase 36 senior care facilities in 2011, and, in 2012, the partners spent $750 million to acquire 68 more nursing homes located in East Coast states. The acquisitions made the two investment firms “one of the United States’ largest standalone skilled nursing portfolios,” according to Senior Housing News, with “more than $1 billion worth of senior care assets in the U.S.”

In 2013, the same two investment firms purchased a “36-property senior housing portfolio for approximately $400 million,” reported Senior Housing News, and in 2014, the two firms struck another deal to buy “14 skilled nursing facilities in the mid-Atlantic for about $150 million,” according to Senior Housing News.

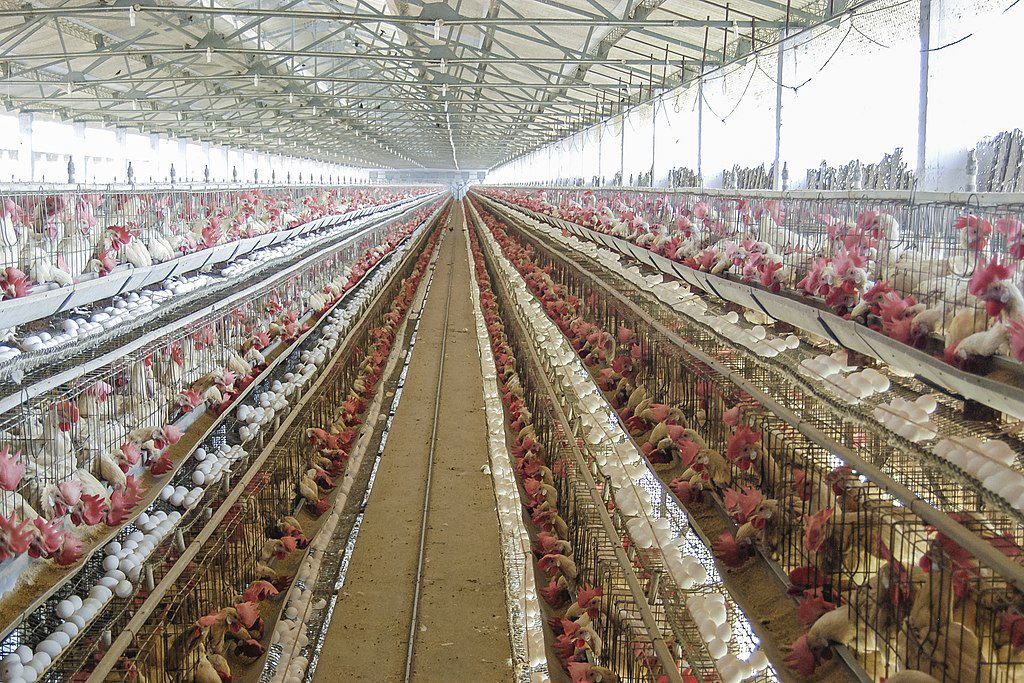

The deals Safanad and Formation Capital struck to acquire senior care facilities are strikingly similar to the business transactions Safanad conducted with Pansophic Learning in the charter school sector, principally, buying up financially struggling service businesses that receive large amounts of public funding—in the case of the senior care sector, from Medicare and Medicaid—and that also happen to include significant holdings of real estate.

The nursing home and senior living facilities industry was struggling financially before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a report by the Pew Charitable Trust. Facilities had been cutting corners for years, skating by with too few staff, due to stagnating wages, and sometimes hiring unskilled workers instead of highly trained personnel.

COVID-19 simply revealed an industry that was already “broken,” reported NBC News, citing “low pay, high turnover, and tough working conditions” as chronic problems in the senior care facilities industry.

Yet the growing presence of private equity investors in the senior care industry has done little to help the industry and appears to have done mostly harm.

A 2020 study3 found that private equity ownership of nursing homes and other kinds of senior living facilities increased costs to the public by 19 percent while shortening the lifespans of patients.

Patients in facilities with substantial private equity backing tended to have less access to nurses, declining mobility, and greater use of antipsychotic medications, the study found. Consequently, “private equity ownership increases short-term mortality by 10 percent,” the authors claimed, “which implies about 21,000 lives lost due to private equity ownership over our sample period.”

As with the for-profit prison industry, many of the problems posed by private investment firms in the senior care industry, according to the study, can be sourced to “high-powered for-profit incentives… [being] misaligned with the social goals of quality care at a reasonable cost.”

The study distinguished private equity for-profit ownership from “generic” for-profit ownership because “private equity ownership confers distinct incentives to quickly and substantially increase the value of their portfolio firms.” It is this form of intense, high-powered profit-maximizing incentives, the authors asserted, “that characterize[s] private equity… [and could lead to] detrimental implications for consumer welfare.”

Investor-driven senior care facilities were especially hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, a 2020 article in the New York Times reported.

“Decades of ownership by private equity and other private investment firms left many nursing homes with staggering bills and razor-thin margins,” according to the article.

“The toll of putting profits first started to show when the outbreak began,” the article continued. “[S]ome for-profit homes were particularly ill equipped and understaffed, which undercut their ability to contain the spread of the coronavirus.”

Among the for-profit operators that appear to have fared poorly in the pandemic is Consulate Health Care, one of the providers that were snapped up by Safanad and Formation Capital in 2014, according to Senior Housing News. In a 2020 report, the Private Equity Stakeholder Project listed Formation Capital as the owner of Consulate Health Care.

Nursing homes operated by Consulate Health Care and Formation Capital have been hotspots for COVID-19 outbreaks, according to numerous news reports from Florida and Virginia. The high incidence of outbreaks prompted, in part, a U.S. House committee to launch an investigation into the country’s five largest for-profit nursing home companies, including Consulate Health Care, Politico reported in 2020.

‘Creative Ways to Wring Profits’

As the New York Times reported in 2020, while senior care facilities often struggle financially, their private equity-backed owners have “found creative ways to wring profits out of them.”

Some of these creative ways include charging their operators “hefty management and consulting fees”; buying the real estate from the operators and then leasing the buildings back to the operators, while upping the rents; and pushing their operators to buy products and services from companies that are controlled by the investors.4

The real estate plays these firms pull off are particularly lucrative, the New York Times noted, because the buildings are often “more valuable than the businesses themselves.”

A 2018 article in the Naples Daily News described how these arrangements work in Consulate Health Care facilities owned by Formation Capital, the state’s largest provider.

Consulate Health Care and Formation Capital both operate a network of other related businesses—including “real estate, management, rehabilitation and other companies”—that they use as subcontractors for the nursing homes they own.

So when “[t]axpayer money flows to Consulate nursing homes,” the article explained, some of the money also goes to subcontractors that are related to the owners, Consulate Health Care and its controlling company, Formation Capital. “[A]nd profits earned go to the chain’s owner, the Atlanta-based private equity firm Formation Capital,” the article stated.

One of the Consulate Health Care nursing homes highlighted in the article pays its owner and management fees to two Consulate companies and also pays its lease payments and rehabilitation service fees to providers that are both related to Formation Capital.

“In each case,” the article said, “the money flows back to Formation Capital and its wealthy investors,” which include Safanad.

Pansophic Learning and Accel Schools operate similar business arrangements that help their organizations maximize their profits, according to a 2021 report by the Network for Public Education (NPE).[2]

Much in the same way Consulate Health Care facilities and Formation Capital push their nursing homes into contracts with their other related businesses, Accel and Pansophic use “a complex web of corporations,” according to NPE, to “control the operations of the school and in doing so, steer business to their related services.”

The report highlighted Accel-managed Broadway Academy, in Cleveland, a charter school previously owned by White Hat Management, according to the Accel Schools contract with the school.

Under the “fees” section in the terms of that contract—originally with for-profit management company Chippewa Community School, LLC, which is now a subsidiary of Accel Schools Ohio LLC—the school, referred to in the contract as the corporation, pays the operator (Accel, by way of its subsidiary Chippewa Community School, LLC) 96 percent of the school’s monthly qualified gross revenue, which is the per-pupil revenue the school receives from the state. In return, Accel is the sole source to provide the school with school staffing and professional development, school management and consulting, textbooks, equipment, technology, student recruitment, building payments, maintenance, custodial service, security, and capital improvements.

In other words, there’s nothing that stops Accel or Pansophic from creating yet more subsidiaries and other related companies that can do business with Broadway Academy. According to the contract, Accel can subcontract services “without the [Broadway Academy] Board’s approval,” and property purchased by Accel “shall remain… [Accel’s] sole property.”

According to NPE, these kinds of contracts, known as “sweeps,” are commonplace in the for-profit charter school industry.

“Sweeps contracts give for-profits the authority to run all school services in exchange for all or nearly all of the school’s revenue,” said the NPE report.

Taxpayer funding for the Broadway Academy that isn’t swept up by Accel’s continuing fee must be deposited into a “Student Enrichment Fund” for “educational services in the areas of student cultural activities[,] … supplemental tutoring services[,] and other programs.” Accel has sole authority to “propose uses for such funds,” and 85 percent “of all Student Enrichment Funds not spent during the fiscal year in which they are received shall be paid over to [Accel].”

While Accel’s contract with Broadway Academy doesn’t include real estate, the authors of the NPE report searched the database of Ohio charter school contracts, called “community schools documents,” and found that “Global School Properties Ohio, LLC holds the leases for many Accel charter schools. The… [landlord] is at the same 1650 Tysons Blvd. address in McLean, Virginia, as Pansophic [Learning].”

Profiting From D- and F-Rated Schools

School choice and charter school advocates are often quick to defend for-profit charter companies and their private investors, arguing that they are “sector agnostic”5 about who owns and operates a school and care only about the school’s “results.”

But what constitutes good results in education is a much-debated topic,6 and studies about the results of for-profit charter schools have found mixed results at best.

A 2017 report from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) found that students who attend for-profit charter schools have weaker growth in math than they would have in a district public school and similar growth in reading.7 Students in nonprofit charter schools experienced stronger academic growth in both subjects than their peers enrolled in for-profit charters. The differences were “significant,” according to the study.

Also in 2017, Chalkbeat reported, “studies comparing for-profit schools to nonprofits and traditional public schools in the same area don’t find consistent differences in performance, as measured by test scores.”

None of these studies examined the performance of Accel Schools or the impact of private equity in the for-profit charter industry.

Nevertheless, an ongoing investigation by Our Schools has revealed charter schools operated by for-profit operators like Accel Schools cycle struggling charter schools through a series of private entities that, in turn, strip the schools of resources, run them at bare-bones costs, and reap whatever assets that remain before handing the schools off to the next private operator, or shutting them down completely. The result is charter operators and their investors may achieve the results they want, while the children caught up in this investor-driven enterprise often have their education significantly disrupted, or even permanently impaired, perhaps with lifelong impact.

References

- Network for Public Education, “Do Charter Schools Profit From Educating Students?” (April 2021).

- Network for Public Education, “Chartered for Profit: The Hidden World of Charter Schools Operated for Financial Gain” (July 2021).

- Atul Gupta, Sabrina T. Howell, Constantine Yannelis, and Abhinav Gupta; NYU Stern School of Business; “Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients? Evidence from Nursing Homes” (2020).

- Matthew Goldstein, Jessica Silver-Greenberg, and Robert Gebeloff; New York Times; “Push for Profits Left Nursing Homes Struggling to Provide Care” (May 7, 2020).

- Nicole Stelle Garnet, Notre Dame Law School, “Sector Agnosticism and the Coming Transformation of Education Law” (April 2017).

- W. James Popham, ASCD, “Why Standardized Tests Don’t Measure Educational Quality” (1999).

- James L. Woodworth et al, Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO), “Charter Management Organizations” (2017).

Jeff Bryant is a writing fellow and chief correspondent for Our Schools. He is a communications consultant, freelance writer, advocacy journalist, and director of the Education Opportunity Network, a strategy and messaging center for progressive education policy. His award-winning commentary and reporting routinely appear in prominent online news outlets, and he speaks frequently at national events about public education policy. Follow him on Twitter @jeffbcdm.

Photo Credit: jonathan mcintosh / Flickr